In our previous post, we examined the pagan backgrounds of Christian practices that take place most often in Sunday worship services. Here we will look at special liturgies of the Christian church and miscellaneous Christian practices that have roots in the goddess and god cults of antiquity.

Special liturgies

Weddings and marriage. According to the late Yale professor John Boswell (164), nuptial blessings in Christianity were required – for the first thousand years – only for (male) priests.  For laypeople, a marriage ceremony in church was an honor and primarily for the free class; slaves married during the Imperial era, but marriages were at the whim of the slaveholder and had no legal status (Glancy, 28). Well into the Middle Ages, marriage for laypeople was primarily secular and a low priority for the church (Boswell, 165).

For laypeople, a marriage ceremony in church was an honor and primarily for the free class; slaves married during the Imperial era, but marriages were at the whim of the slaveholder and had no legal status (Glancy, 28). Well into the Middle Ages, marriage for laypeople was primarily secular and a low priority for the church (Boswell, 165).

Ancient practices around weddings varied between locations and across time. But some of the familiar actions associated with them have pagan roots. In ancient patriarchal societies like Greece and Rome, marriage had to do with the woman/bride joining the man/groom and his family, with the primary purpose of procreation. The woman usually left her home and made her way to the groom’s; the bride and groom would clasp hands; specific words and prayers were said; and a contract would be signed (Ferguson, 67ff). Much of this, of course, made it into Christian rites, and we are primarily talking about heterosexual unions.

Boswell, though, as well as Brandeis professor Bernadette Brooten have written entire books on same-sex unions and marriage ceremonies in Christianity. We have explored some of this previously.

Boswell, though, as well as Brandeis professor Bernadette Brooten have written entire books on same-sex unions and marriage ceremonies in Christianity. We have explored some of this previously.

When societies venerated the feminine force – human women, female deities and animals, Mother Earth, etc. – we see something a bit different when it comes to marriage, even though the main goal still had to do with procreation. According to Marija Gimbutas (18), Neolithic and other prehistoric peoples honored the so-called hieros gamos, or sacred marriage – the sexual linking of male and female to ensure “the well-being and fertility of the land and its inhabitants.” This is a broader concept than the more traditional goals of producing human offspring to keep a dynasty going or populating a kingdom.

Rituals enacting the sacred marriage in prehistoric Greece, the Near East, India, and elsewhere were restricted to a few special people: priestesses representing the goddess and priests representing the year god (Gimbutas, 19). Goddess-oriented rituals had the bridegroom – the male – come “in his ship from overseas to fulfill the sacred wedding in the sanctuary of the goddess.” The priestess, representing the bride, welcomed the groom to her quarters, and the divine wedding took place in her temple (Gimbutas, 118-19).

Marriage is yet another example of how Christianity and the West substituted male supremacy for respect for the feminine principle and human women. We may love weddings, but it might behoove us to ponder the joining of human beings in marriage and similar rites from the perspective of our forebears’ worship of a female deity, when the goal served both the survival of human beings and the health of the natural world.

Funerals, burial rites and the life-death-regeneration cycle. Human beings have long needed to dispose of their dead, honor them, and try to figure out what happens after the death event. Christian theology and rites, of course, are centered on the death and resurrection of Jesus and the hope of life in Christ after death. In recalling the ancient polytheistic roots of Christianity and the West, however, we will “look behind the curtain” to enlarge our perspective.

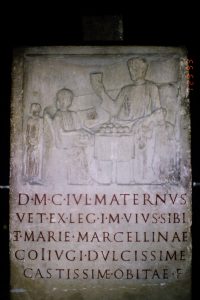

The custom of erecting monuments in cemeteries is one practice with ancient roots. Funerary monuments from antiquity bear images and inscriptions honoring the deceased.  This monument to a veteran, G. Julius Maternus, and his wife, discovered in Bonn and now housed in the Römisch-Germanisches Museum in Cologne, dates to the early 2nd c. CE. The monument bears the carving of a funerary banquet on top. The banquet was a very prominent theme on funerary monuments – probably indicating a positive belief that the afterlife was a cheery place full of abundance.

This monument to a veteran, G. Julius Maternus, and his wife, discovered in Bonn and now housed in the Römisch-Germanisches Museum in Cologne, dates to the early 2nd c. CE. The monument bears the carving of a funerary banquet on top. The banquet was a very prominent theme on funerary monuments – probably indicating a positive belief that the afterlife was a cheery place full of abundance.

The banquet image probably also reflects actual ritual practices associated with funerals and appears in the Roman catacombs. What has been described as a “rousing funerary banquet” is from the catacomb of Saints Peter and Marcellinus in Rome. Its date is important: 4th c. CE, well into the Christian era. As we have seen previously, the catacombs were underground burial places for several centuries, and Jews, pagans and Christians all used them. Contrary to what we may have learned, the catacombs were most likely not hiding places for persecuted Christians: they were too well-known, and the small space could not have accommodated large gatherings.

The funerary banquet image indicates a longstanding link between death, burials and food. Although we can never truly know what Neolithic peoples may have believed, Gimbutas and others learned through excavations in Europe and elsewhere that the realm of the nature goddess was paramount. She was understood as the all-powerful life-giver who provided water, grain, grapes, and all forms of sustenance. But our ancient ancestors also understood that life included death – in itself powerful, often sudden and tragic, and everywhere – and it was the goddess who presided over death.  The main images of death from prehistory include the goddess as linked to the vulture, owl, cuckoo, hawk, dove, the howling dog, and the stiff nude figure. The vulture feeds on carrion; the owl and howling dog were viewed as harbingers of death; people looked at the cuckoo, hawk, and dove as omens of death and spirits of the dead; and the “stiff nude” female figurines have been found throughout Old Europe (Gimbutas, especially 187-211).

The main images of death from prehistory include the goddess as linked to the vulture, owl, cuckoo, hawk, dove, the howling dog, and the stiff nude figure. The vulture feeds on carrion; the owl and howling dog were viewed as harbingers of death; people looked at the cuckoo, hawk, and dove as omens of death and spirits of the dead; and the “stiff nude” female figurines have been found throughout Old Europe (Gimbutas, especially 187-211).

However in the ancient mindset, death was not the final word: in the natural world, death was regularly followed by regeneration – through the birth of animals and human beings, plant growth, etc. Related to it all was the powerful, undeniable female force.

Our ancestors thus had a positive take, in many ways, on the life-death-regeneration cycle. While Christianity generally couches this in terms of our male God, the man Jesus and his victory over death, and a Holy Spirit who has traditionally been designated as male, our agrarian forebears viewed the cycle in terms of the nature goddess. Even as late as some of the Christian catacomb art we witness a positive, life-affirming sensibility around death, deliverance, nature and peace.

The sprinkling rite – or asperges (from Latin aspergere, to sprinkle) – may be less familiar to Christians in some denominations.  The priests come down the aisles in a service, usually during the Easter season or at baptisms, using an aspergillum (or reasonable facsimile like an evergreen branch) to sprinkle parishioners with holy water in commemoration of baptism. This rite is done more frequently in Roman Catholic, Orthodox, and other Christian settings, and there are various actions associated with the ritual.

The priests come down the aisles in a service, usually during the Easter season or at baptisms, using an aspergillum (or reasonable facsimile like an evergreen branch) to sprinkle parishioners with holy water in commemoration of baptism. This rite is done more frequently in Roman Catholic, Orthodox, and other Christian settings, and there are various actions associated with the ritual.

Water is at the base of the asperges rite; as we have seen, water is closely related to the female life force from prehistoric times. We can see some of the nature-related roots of the asperges rite in the Jewish Psalms (and of course Christianity appropriated Hebrew Scriptures in its practices). The sprinkling rite comes from a verse of one of the Psalms (51:7 in several Protestant versions, 50:9 in Latin Vulgate): “Purge me with hyssop, and I shall be clean; wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow.” Thus washing and purity are primary in the sprinkling rite.

The sprinkling rite lives on in arenas that are more female-oriented: “Aspergilla are also used in modern paganism, particularly to cleanse a ritual area in Wicca, as part of a spell, or during a Wheel of the Year festival in contemporary Witchcraft. Lunarized water, saltwater, or rainwater are most typically used.”

Sprinkling, water, baptism: all hearken back to a time when our ancient ancestors acknowledged the power and supremacy of the female life force.

Ordination ceremonies. In the Christian denominations that practice “apostolic succession,” that is, the teaching that bishops, especially, represent a direct, uninterrupted line of continuity from the earliest apostles of Jesus Christ, ordination rites can be very impressive – featuring long, colorful processions of robed participants, with the ministers and people singing hymns.  The branches of Christianity that accept apostolic succession include Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Old Catholic, Swedish Lutheran, and Anglican/Episcopal. In these churches deacons and priests are also ordained.

The branches of Christianity that accept apostolic succession include Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, Old Catholic, Swedish Lutheran, and Anglican/Episcopal. In these churches deacons and priests are also ordained.

Ordination ceremonies in the Episcopal Church can be used an illustration of some elements that often appear in ancient coronation ceremonies. Ordinations in the Episcopal Church, which appear to have been instituted around 1550, describe these elements: “the taking of special vows . . . [and] the investing and presentation of regalia.” The placing of a crown on the ruler’s head in a coronation is similar to laying hands on the heads of the newly ordained and the placing of the miter on the new bishop’s head. In the Roman Empire, emperors started to claim that they were divine, so early church leaders promoted Jesus the Christ as a divine man in competition with the emperors. The symbolism of clothing Jesus’ ministers on earth during their ordination reflects this aspect of rulers’ closeness to and even equation with the Divine.

When a deacon or priest is ordained in the Episcopal Church and other Christian denominations, he (also “she” in some churches, although not in Roman Catholic, Orthodox, or Southern Baptist branches) generally goes through training (such as in a seminary), is supported by the larger church and, during the ceremony, professes loyalty. The Christian ceremony includes some version of the following “examination:”

Celebrant (usually a bishop): “Will you be loyal to the doctrine, discipline, and worship of Christ as this Church has received them? And will you, in accordance with the canons of this Church, obey your bishop and other ministers who may have authority over you and your work?”

Ordinand: “I am willing and ready to do so; and I solemnly declare that I do believe the Holy Scriptures of the Old and New Testaments to be the Word of God, and to contain all things necessary to salvation; and I do solemnly engage to conform to the doctrine, discipline, and worship of The ____ Church.”

Even with the recent ordination of women, the church is far removed from the great reverence that ancient people had for the all-powerful feminine life force.  Today, ecclesiastical leaders and the “people in the pews” grant deacons, priests and bishops a great deal of responsibility and authority in the church. Laypeople always hope that the church has done its job in choosing their leaders and that these ministers will live up to the highest ethical and moral standards. Christianity has endured for two millennia because and sometimes in spite of its hierarchical structure and these ordained ministries. It is an interesting exercise to ponder the parallels between the “elevation” of Christian ministers and the coronation of emperors – many of whom we know to have been corrupt, flawed, cruel and often downright evil. Sadly, we also know that too many ordained Christians – until recently almost exclusively male – have been similarly flawed.

Today, ecclesiastical leaders and the “people in the pews” grant deacons, priests and bishops a great deal of responsibility and authority in the church. Laypeople always hope that the church has done its job in choosing their leaders and that these ministers will live up to the highest ethical and moral standards. Christianity has endured for two millennia because and sometimes in spite of its hierarchical structure and these ordained ministries. It is an interesting exercise to ponder the parallels between the “elevation” of Christian ministers and the coronation of emperors – many of whom we know to have been corrupt, flawed, cruel and often downright evil. Sadly, we also know that too many ordained Christians – until recently almost exclusively male – have been similarly flawed.

Other practices

Healing. While we may not necessarily associate healing with the church in general, it is part of the practice in some parishes and might include prayers for healing during weekly services and a Pastoral Care Ministry, for instance. Some parishes employ a parish or community nurse, a position that is now officially recognized as a specialty by the American Nurses Association. In addition, several colleges offer courses in Parish Nursing.

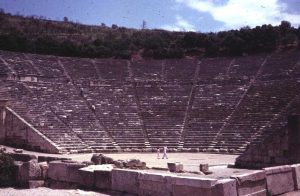

Earlier, we saw how ancient cults had a healing component. We highlighted the examples of Asklepios, his sister/daughter Hygieia, Artemis and Isis. (One of Asklepios’ primary healing centers was at Epidauros, its theater pictured here.)

We also saw how healing was connected with water – water from spas and mineral springs, water that sustains life and promotes growth, water associated with purifying baths, etc. We were reminded that water was associated in prehistoric times with the goddess, Mother Earth, and women.

Until recently, physicians in Western society have been primarily male, and the medical establishment has rested on an androcentric foundation. This has not always gone well for women, children, gender-nonconforming persons, and other vulnerable people – including many men. Evidence from prehistory and the Graeco-Roman world reminds us that healing, religion, water and the female life force were inextricably linked; we would do well to reclaim some of the wisdom of that perspective.

Ashes on Ash Wednesday. In Christianity, when the priest marks a cross of ashes on worshippers’ foreheads, Ash Wednesday begins the penitential season of Lent. As written in the Book of Common Prayer (BCP, 265), the priest prays, “Almighty God, you have created us out of the dust of the earth: Grant that these ashes may be to us a sign of our mortality and penitence, that we may remember that it is only by your gracious gift that we are given everlasting life.” As the ashes are imposed, s/he continues, “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”

As Walker explains (118), this rite originated with the Vedic sages of ancient India. Their fire god Agni was believed to have given his seed to the world in the form of ashes, so bathing the body in ashes was thought to remove any trace of past transgressions. The Romans bathed in ashes at the New Year festival of atonement, in March, the first month of their year. “The Christian church adopted the same date and converted it into Ash Wednesday.” The Romans lived it up the day before (our Mardi Gras), believing that any sins committed in the previous 24 hours would be forgiven by bathing in ashes.

Labyrinth. Finally, many moderns have walked a labyrinth. As we saw earlier, this practice has many levels of meaning, one of which is a symbolic pilgrimage to the Holy Land – the home of Jesus of Nazareth – and back again (Walker, 96).

The meaning of the word “labyrinth” is vague. A definition that resonates with Walker (95-96) is “a word of pre-Greek (Minoan) origin absorbed by Classical Greek [that] is perhaps related to the Lydian labrys (‘double-edged axe’, a symbol of royal power . . . the labyrinth was originally the royal Minoan palace on Crete and meant ‘palace of the double-axe’).” In addition, Gimbutas (xx) notes that Minoan Crete has been described by Riane Eiseler as a “gylany” – a culture where both sexes were equal – and as a goddess-centered “social order in which women as heads of clans or queen-priestesses played a central part.”

Once again we see a vital, ancient connection with the feminine life force: labyrinths, mountains and caves, the goddess, Mother Earth, human anatomy, the womb-tomb, ritualistically “dying” and being born again anew. Our ancient ancestors were deeply in touch with everything around and in them, and the labyrinth ritual was a part of that.

Once again we see a vital, ancient connection with the feminine life force: labyrinths, mountains and caves, the goddess, Mother Earth, human anatomy, the womb-tomb, ritualistically “dying” and being born again anew. Our ancient ancestors were deeply in touch with everything around and in them, and the labyrinth ritual was a part of that.

The next time we see or even walk a labyrinth, perhaps we could direct our grateful thoughts to Mother Earth and the feminine life force all around us!

Conclusion

Many other Christian practices have ancient antecedents – veneration of the cross, burning/lighting candles, praying the rosary, sacred dance, decorating the Christmas tree. To contemplate the pagan roots of Western civilization is not only to enrich our understanding of our own history but also, more importantly, to raise our level of respect: for our ancient ancestors – who possessed much wisdom that we have lost – and for the feminine life force of women and in all of nature.

Resources (for both posts)

Abrahamsen, Valerie A. Goddess and God: A Holy Tension in the First Christian Centuries. Marco Polo Monographs 10. Warren Center, PA: Shangri-La Publications, 2006.

Abrahamsen, Valerie A. Women and Worship at Philippi: Diana/Artemis and Other Cults in the Early Christian Era. Portland, ME: Astarte Shell Press, 1995.

Boswell, John. Same-sex Unions in Premodern Europe. New York: Villiard Books, 1994.

Brooten, Bernadette J. Love Between Women: Early Christian Responses to Female Homoeroticism. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1996.

Campbell, Joseph. The Masks of God: Primitive Mythology. New York: Penguin Books, 1982; first ed., Viking Press, 1959.

Church Pension Fund. The Book of Common Prayer. New York: The Church Hymnal Corporation, 1986.

Collart, Paul and Pierre Ducrey. Philippes I: Les reliefs rupestres. Athens and Paris: BCH Supplement 2, 1975.

Eisler, Riane. The Chalice and the Blade: Our History, Our Future. San Francisco, Harper & Row, Publishers, 1987.

Ferguson, Everett. Backgrounds of Early Christianity, 2nd ed. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1993.

Gimbutas, Marija. The Language of the Goddess. New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 1991.

Glancy, Jennifer A. Slavery in Early Christianity. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2006. Original hardcover edition Oxford University Press, 2002.

Herrin, Judith. Ravenna: Capital of Empire, Crucible of Europe. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2020.

Kraemer, Ross Shepard and Mary Rose D’Angelo, eds. Women and Christian Origins. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Lefkowitz, Mary R. and Maureen B. Fant. Women’s Life in Greece and Rome. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982.

Mitchell, John. The Earth Spirit. London: Thames and Hudson, 1975; New York: Avon Books, 1975.

Pervo, Richard I. Dating Acts: Between the Evangelists and the Apologists. Santa Rosa: Polebridge Press, 2006.

Reis, Patricia. Through the Goddess: A Woman’s Way of Healing. New York: Continuum, 1991.

Sjöö, Monica and Barbara Mor, The Great Cosmic Mother. San Francisco: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1987.

Snyder, Graydon F. Ante Pacem: Archaeological Evidence of Church Life Before Constantine, revised edition. Macon, GA: Mercer University Press, 2003.

Underwood, Guy. The Pattern of the Past. London: Museum, Press, 1969; London: Abacus, 1972.

Walker, Barbara G. The Woman’s Dictionary of Symbols and Sacred Objects. San Francisco: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1988.