Introduction

Nurses throughout the United States, and indeed throughout the world, have been on the front line of care during the pandemic.  They are among the heroes in our communities, but we know that they are facing severe challenges as individuals and as a profession. There has been a nursing shortage for years, and that has only been exacerbated by the pandemic. According to the University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences, “Most nurses are dedicated to helping patients however they can; [but because of the pandemic] it’s stressful to be thrown into a new area of nursing on short notice – especially an area as demanding as critical care.”

They are among the heroes in our communities, but we know that they are facing severe challenges as individuals and as a profession. There has been a nursing shortage for years, and that has only been exacerbated by the pandemic. According to the University of St. Augustine for Health Sciences, “Most nurses are dedicated to helping patients however they can; [but because of the pandemic] it’s stressful to be thrown into a new area of nursing on short notice – especially an area as demanding as critical care.”

The profession is a long-established career, especially for women. According to US census data, “… the largest health care occupation is registered nurses, with over 2.4 million workers, followed by nursing, psychiatric and home health aides (1.2 million). Women make up more than 85% of workers in both of these large occupations.…. There are about 763,000 physicians and surgeons working full-time, year-round and about a third are women.”

When it comes to earnings, there has been some progress for women in healthcare positions since 2000, but the gains have been uneven. “Most of the positive changes in median earnings are found in higher-educated occupations, leaving workers in lower-educated occupations, such as nursing, psychiatric and home health aides, with little or no gains in median earnings since 2000.”

When it comes to earnings, there has been some progress for women in healthcare positions since 2000, but the gains have been uneven. “Most of the positive changes in median earnings are found in higher-educated occupations, leaving workers in lower-educated occupations, such as nursing, psychiatric and home health aides, with little or no gains in median earnings since 2000.”

This means that, despite gains in the number of women working in previously male-dominated medical professions (physicians, surgeons, pharmacists, etc.) and some increase in earnings, men still dominate the US healthcare system in many ways.

Given that situation, an historical overview of the healing professions can enhance the respect nurses deserve and empower them and even women overall. Here we will examine the healing aspects of goddesses in antiquity and prehistory, their connection with the healing roles of women, and how reverence for the female principle – Mother Earth and her manifestation as the goddess – can help create a peaceful, prosperous civilization for all.

Healing Deities in the Ancient World

In antiquity and prehistoric eras, goddesses and gods were venerated everywhere and were served by both women and men. A brief look at one male and three female deities from the Graeco-Roman era will show their healing nature and how that aspect played out in their cults.

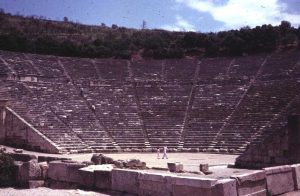

Asklepios. The god Asklepios was one of the most popular deities in the Graeco-Roman world and was sought out for a wide array of health problems. In his mythology, he was the son of the god Apollo and the human woman, Coronis.  He was thought to have been born at the Greek city of Epidauros, site of his most important sanctuary, and to have died as a mortal then come back to life again. By the second century CE, “his benefactions as a miraculous healer … were celebrated in hundreds of temples across the Roman empire,” (Robinson, 475), including Corinth. (As we’ve seen earlier, Corinth was a city in northern Greece to which St. Paul wrote several letters. Corinth and St. Paul are significant not only because of the early Christian context but also because of Christianity’s significant impact on Western civilization.)

He was thought to have been born at the Greek city of Epidauros, site of his most important sanctuary, and to have died as a mortal then come back to life again. By the second century CE, “his benefactions as a miraculous healer … were celebrated in hundreds of temples across the Roman empire,” (Robinson, 475), including Corinth. (As we’ve seen earlier, Corinth was a city in northern Greece to which St. Paul wrote several letters. Corinth and St. Paul are significant not only because of the early Christian context but also because of Christianity’s significant impact on Western civilization.)

Hygieia. Hygieia, daughter of Asklepios, and her sister Panacea may have been personifications of the Great Mother Goddess’ breasts. The Greek caduceus – the staff with the entwined snake, the international symbol of the medical profession – was displayed in the healing temples of Hygieia and Panacea and represented physical and spiritual healing.  The snake was most likely a hold-over from the prehistoric goddesses from Crete, Delphi, Old Europe, and elsewhere (Reis, 163): the snake symbolized healing and came to have evil or dangerous connotations only later in Jewish and Christian mythology associated with Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. Hygieia came to be secondary to Asklepios, even though early on she was probably the original and most powerful healing deity.

The snake was most likely a hold-over from the prehistoric goddesses from Crete, Delphi, Old Europe, and elsewhere (Reis, 163): the snake symbolized healing and came to have evil or dangerous connotations only later in Jewish and Christian mythology associated with Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden. Hygieia came to be secondary to Asklepios, even though early on she was probably the original and most powerful healing deity.

In later myth, Hygieia became the goddess of mental health. Ancient peoples believed that bodily sickness and psychic pain were inseparable: physical symptoms were seen as the outer bodily manifestation of an inner psychic disturbance. Hygieia was thus appealed to in relation to the emotional and spiritual aspects of healing physical illnesses, and she often worked through dreams (Reis, 163).

Artemis. Artemis, known also by her Roman name, Diana, was wild, free and unattached. She loved the woods, animals, and children, but was also at times the protector of whole cities. She was associated with healing, especially of women and children, at a number of sites, as early as the seventh century BCE.

The Greek city of Philippi was site of one of her major cults in the late second to early third century CE and was associated with St. Paul in the first century. The unique rock reliefs on the acropolis hill at Philippi, probably carved (perhaps by women) around 200 CE, depict Diana in various poses that suggest her role in healing. It is probably also attested by a votive inscription on the acropolis hill near a pair of carved eyes and two crescents: “Galgestia Primilla has rightly paid off with pleasure (this) votive to Diana on behalf of (her) daughter.” This may refer to a cure having to do with the eyes or to the goddess having seen the girl’s distress then healed her (Abrahamsen, Women and Worship, 30, 137).

The city of Ephesus in Asia Minor also shows connections between healing, a female deity and St. Paul.  Artemis was the city’s protector deity: the crown of her cult statue, now at the Vatican, is a city wall. But this famous statue also shows her torso covered with breasts, even though in most other Artemis statues from antiquity she is shown as a lithe, athletic deity with bow and arrow. That the Ephesus status with its many breasts most likely indicated an abundance of mother’s milk – milk being known in antiquity to have healing powers – shows that Artemis’ cult there probably had a viable healing component, which accounted for much of its popularity. As we might expect, though, the power and popularity of this deity bothered early Christians: the New Testament Acts of the Apostles describes St. Paul as being in heavy competition with Artemis of Ephesus. Tradition, following that perspective, has led most (male) historians to fail to mention milk; rather, they interpret Artemis’ breasts primarily as a vague representation of fertility instead of an essential food source that sustained and sustains the entire human race.

Artemis was the city’s protector deity: the crown of her cult statue, now at the Vatican, is a city wall. But this famous statue also shows her torso covered with breasts, even though in most other Artemis statues from antiquity she is shown as a lithe, athletic deity with bow and arrow. That the Ephesus status with its many breasts most likely indicated an abundance of mother’s milk – milk being known in antiquity to have healing powers – shows that Artemis’ cult there probably had a viable healing component, which accounted for much of its popularity. As we might expect, though, the power and popularity of this deity bothered early Christians: the New Testament Acts of the Apostles describes St. Paul as being in heavy competition with Artemis of Ephesus. Tradition, following that perspective, has led most (male) historians to fail to mention milk; rather, they interpret Artemis’ breasts primarily as a vague representation of fertility instead of an essential food source that sustained and sustains the entire human race.

Isis.  Isis, a goddess that originated in Egypt, was wife (and sister) of Osiris/Serapis and mother of Horus. Isis and Serapis were the most popular and widespread of the foreign deities in the Roman era, and the iconography of Isis suckling Horus (another link to milk) inspired artistic representations of the Christian Virgin Mary holding the infant Jesus.

Isis, a goddess that originated in Egypt, was wife (and sister) of Osiris/Serapis and mother of Horus. Isis and Serapis were the most popular and widespread of the foreign deities in the Roman era, and the iconography of Isis suckling Horus (another link to milk) inspired artistic representations of the Christian Virgin Mary holding the infant Jesus.

The cult of Isis and Serapis was comprised of women priestesses and other officiants (including men; theirs was a very egalitarian cult). Isis cared especially for children and was invoked in all matters pertaining to motherhood. During initiation rites into her cult, the priest declared that the initiation was “like a voluntary death and a difficult restoration to health” (Bleeker, 39).

Isis was often depicted with a sistrum, a kind of rattle, and a situla, a small bucket for water or milk. Again, most historians do not mention Isis’ connection with healing or suggest that the bucket for water or milk might have been associated with healing. Yet both water and mother’s milk were used extensively in healing rites.

The Prehistoric Nature Goddess and Implications for Nursing

The healing gifts of the female deities of the Graeco-Roman era had their roots deep in prehistory when agrarian peoples equated all of life – nature, women and female animals, and even the heavens – with the female principle.

The prehistoric cultures of Old Europe have yielded thousands of artifacts that testify to this absolute reverence for female deities and human women. According to the late archaeologist Marija Gimbutas, these societies – which endured for millennia – were true civilizations, basically peaceful and highly accomplished artistically. The archaeological evidence from Paleolithic and Neolithic sites shows that representations of male deities were rare, and graves of men were less lavish than those of women. There is very little evidence of any kind for violence – no weapons, few broken bones, no signs of warfare – and art, religion and astrology were closely connected.

In these prehistoric societies, healing was long associated with water – water from spas and mineral springs, water that sustains life and promotes growth, water associated with purifying baths, etc. And water was traditionally in the domain of the goddess, the “life-giving moisture of the Goddess’ body,” according to Gimbutas (Language, 3).

In these prehistoric societies, healing was long associated with water – water from spas and mineral springs, water that sustains life and promotes growth, water associated with purifying baths, etc. And water was traditionally in the domain of the goddess, the “life-giving moisture of the Goddess’ body,” according to Gimbutas (Language, 3).

Also, all life depends on the water of springs, streams, rivers, rain and dew, and prehistoric peoples recognized that water was essential to growth, healing and health. Our Paleolithic and Neolithic ancestors depicted water – that generative source – with zigzag lines and geometric symbols on figurines, sculptures, vases, altar pieces, and cult vessels. These symbols were often found in conjunction with water bird images – ducks, geese, cranes, and swans – and all were linked to the prehistoric nature goddess as well as to female moisture and amniotic fluid (Language, 3, 19-21).

The veneration of healing goddesses went hand-in-hand with respect for human women and their powers to heal. The example of these ancient societies should do the same for our world: if these cultures can honor the feminine principle and human women for millennia and thus create healthy, prosperous and peaceful societies, we can, too.

For nurses to see themselves as legitimate heirs of ancient healing women and goddesses, and of practices that heal both individuals and communities, is to empower them in a society that desperately needs their compassion, expertise, authority and strength.

Resources

Abrahamsen, Valerie A. Women and Worship at Philippi: Diana/Artemis and Other Cults in the Early Christian Era. Portland, MD: Astarte Shell Press, 1995.

Abrahamsen, Valerie. “Women in Early Christianity,” in Bruce M. Metzger and Michael D. Coogan, eds., Oxford Companion to the Bible, 814-18. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Bleeker, C.J. “Isis and Hathor,” in Carl Olson, ed. The Book of the Goddess Past and Present, 39. New York: Crossroad, 1983.

Ferguson, Everett. Backgrounds of Early Christianity, 2nd ed. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1993.

Gimbutas, Marija. The Civilization of the Goddess, ed. Joan Marler. San Francisco: HarperSan Francisco, 1991.

Gimbutas, Marija. The Language of the Goddess. San Francisco: Harper and Row, Publishers, 1989.

Heyob, Sharon Kelly. The Cult of Isis Among Women in the Graeco-Roman World. Leiden: Brill, 1975.

Humphreys, Sarah C. The Family, Women and Death. London and Boston: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1983.

Lefkowitz, Mary R. and Maureen B. Fant. Women’s Life in Greece and Rome. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982.

Olson, Carl, ed. The Book of the Goddess Past and Present. New York: Crossroad, 1983.

Pomeroy, Sarah. Goddesses, Whores, Wives and Slaves: Women in Classical Antiquity. New York: Schocken Books, 1975.

Pomeroy, Sarah, ed. Women’s History and Ancient History. Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1991.

Reis, Patricia. Through the Goddess: A Woman’s Way of Healing. New York: Continuum, 1991.

Schussler Fiorenza, Elisabeth. In Memory of Her. New York: Crossroad Publishing Co., 1983.

Robinson, Thomas L. “Asclepius, Cult of,” Anchor Bible Dictionary, 475. New York: Doubleday, 1992.

Walsh, Elizabeth Miller. Women in Western Civilization. Cambridge, MA: Schenkman Publishing Co., Inc., 1981.

———————

This post is adapted from Valerie Abrahamsen, “The Goddess and Healing: Nursing’s Heritage from Antiquity,” Journal of Holistic Nursing, Vol. 15, No. 1 (March 1997) 9-24.