As a spiritual practice, and for positive mental health, it is good to give thanks – to express gratitude, whether to a powerful God, our guardian angels, our families and friends, and our teachers and other generous givers of wisdom. We can perhaps also add so many other people – and even inanimate “beings” – to which we owe so much: essential employees and first responders on whom we have come especially to depend over the past two years, those heroes who have died for causes greater than themselves, the fruits of the earth that keep us alive, the heavens that give us sun and rain, institutions that exist to help others, and so many more.

For many of us, sincere gratitude is at the base of our national Thanksgiving Day holiday, and that is to be celebrated.

We as a nation are beginning to realize, however, that the traditional narrative we have inherited is neither simple nor just. While the right wing of our political conversation argues that learning about and teaching the more negative and far less savory aspects of our national story is somehow an affront to those of us who are white, a more nuanced, inquisitive, balanced and fair perspective is that confronting our shortcomings is not only richer and more interesting and complete but also helps bring us closer to our “more perfect union,” as stated in the Preamble to our Constitution.  Americans who fear this larger, more expanded narrative should ask themselves what it is, exactly, that they fear…

Americans who fear this larger, more expanded narrative should ask themselves what it is, exactly, that they fear…

In this season of thanksgiving, and in this time of challenging social and political division and anxiety, let us pause to consider the Wampanoags, the Native people who had inhabited what is now present-day Massachusetts and Eastern Rhode Island for more than 12,000 years. Many of us know the basic Thanksgiving story that the group’s leader, Massasoit (chief Ousamequin), sometime in the fall of 1621, provided food for a several-days feast for the settlers of Plymouth Plantation, thus saving many of those settlers from certain death.

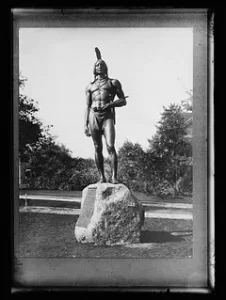

According to Mayflower 400 UK, in 1970, the 350th anniversary of the Mayflower’s sailing, the Wampanoag leader Frank James was asked to speak on the anniversary of Thanksgiving. Despite being told that his speech “was inappropriate and inflammatory,” he was not deterred. “Supporters followed James to hear him give his original speech on Cole’s Hill, next to the statue of Ousamequin.”  Thus was born the first National Day of Mourning, which continues today in Plymouth, Massachusetts, on the same day as Thanksgiving.

Thus was born the first National Day of Mourning, which continues today in Plymouth, Massachusetts, on the same day as Thanksgiving.

Let us heed James’ sobering words: “This action by Massasoit was perhaps our biggest mistake. We, the Wampanoag, welcomed you, the white man, with open arms, little knowing that it was the beginning of the end.” In the decades and centuries that followed, the Wampanoags and other Native groups were decimated by slavery, disease, war, broken treaties, and other actions at the hands of the white settlers.

Despite this tragic, heartbreaking devastation, members of the Wampanoag community live among us. Approximately 4,000-5,000 Wampanoag currently live in New England and “still continue their way of life through oral traditions, ceremonies, the Wampanoag language, song and dance, social gatherings, hunting and fishing.”

What are some practical, doable ways that we can honor the Wampanoags and other Native Americans, both as expressions of empathy and support but also for a larger ultimate goal – to “form a more perfect union” that would benefit all of us?

- Read the clear, beautifully-written, comprehensive history of the Wampanoags produced by Mayflower 400 UK. Mayflower 400 was “an honest, broad and inclusive commemoration of the ship’s sailing from England to America and its often challenging legacy.” The commemoration not only marked the 400th anniversary year from 2018 through 2021 but was also “a shared history of four nations – the Wampanoag, UK, USA and Netherlands.”

- Support Native groups who are seeking state and federal recognition of their existence and rights. The Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe is particularly active in this regard. According to its website, “the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribe, also known as the People of the First Light, has inhabited present day Massachusetts and Eastern Rhode Island for more than 12,000 years.

After an arduous process lasting more than three decades, the Mashpee Wampanoag were re-acknowledged as a federally recognized tribe in 2007. In 2015, the federal government declared 150 acres of land in Mashpee and 170 acres of land in Taunton as the Tribe’s initial reservation, on which the Tribe can exercise its full tribal sovereignty rights. The Mashpee tribe currently has approximately 2,600 enrolled citizens.”

After an arduous process lasting more than three decades, the Mashpee Wampanoag were re-acknowledged as a federally recognized tribe in 2007. In 2015, the federal government declared 150 acres of land in Mashpee and 170 acres of land in Taunton as the Tribe’s initial reservation, on which the Tribe can exercise its full tribal sovereignty rights. The Mashpee tribe currently has approximately 2,600 enrolled citizens.” - Support legislation that enhances the rights and opportunities for Native Americans to exercise their right to vote. Draconian voter suppression laws are being passed throughout this country – with no indication whatsoever that they are necessary because there is no widespread fraud – and those laws tend to work especially against people of color.

- Educate ourselves about things going on in our communities that target or otherwise disadvantage Native Americans. One dramatic and head-shaking example is the case of large numbers of Indigenous women going missing or being murdered in Wyoming. In a recent report issued by the University of Wyoming, “between 2011 and September 2020, 710 Indigenous people were reported missing across Wyoming, and that between 2000 and 2020, Indigenous homicide victims accounted for 21% of all homicides, though they make up only 3% of the state’s population” and received far less media coverage than similar white victims.

The problem is not unique to Wyoming, of course; all of us need to join advocacy efforts and federal and state agencies to combat not only violence against Indigenous peoples and other victims but also the absence of adequate coverage by journalists and the media.

The problem is not unique to Wyoming, of course; all of us need to join advocacy efforts and federal and state agencies to combat not only violence against Indigenous peoples and other victims but also the absence of adequate coverage by journalists and the media. - Support and attend cultural activities sponsored by Native groups in our communities. The Abenaki people in Vermont, for instance, sponsor a number of activities throughout the year, with many open to the public.

- Learn about and support efforts in our communities and states to honor Native Americans in legislative actions (e.g., Indigenous Peoples’ Day) and state-funded commemorative plaques to add Native place names to signs, for example, as was done in Vermont by Republican Gov. Phil Scott in 2020: Scott “signed into law a proposal to add Abenaki place names to signs in state parks. By March, the state’s Commission on Native American Affairs will come up with a list of places and landmarks that have Abenaki names. Those names will then be included along with English names in state parks.”

- Support schools’ efforts to educate students about Native peoples, including teaching a more nuanced and truthful (although possibly painful) Thanksgiving story.

Find ways to allay fears of those citizens in our midst who might protest these efforts because they might “erase” white or majority culture.

Find ways to allay fears of those citizens in our midst who might protest these efforts because they might “erase” white or majority culture. - Support Native and other candidates of color or from underrepresented communities who are running for local, state and national offices.

In short, with all of these suggestions and many others, the goal is not to shame white people or erase white or European history but rather to present a more balanced account that is fact-based and fairer to people who have traditionally been kept in the shadows in our society. If we white people take a moment to empathetically put ourselves in the shoes of those who have effectively been silenced, oppressed, harmed and/or betrayed for centuries, we might well realize how painful that would be and counter to the idealistic values of our nation – and how we would legitimately want that situation to change.