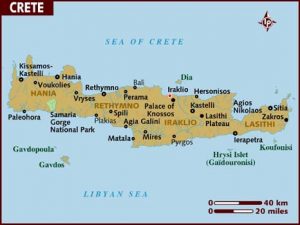

Another archaeological discovery in Greece – this time from the island of Crete – adds to the corpus of information about the roles and influence of women in antiquity. As reported in Archaeology and Science Magazine, the body of a woman was unearthed in the city of Eleutherna, on the slopes of Mt. Ida.  The woman’s skeleton led to an intriguing mystery. When her bones were closely examined scientifically, unusual details were noticed. According to writer Michael Price of Science Magazine, “Compared with other women at the Orthi Petra burial site, she was unusually muscular, especially on the right side of her body. She had also worn out the cartilage in her knee and hip joints, which would have made moving a painful, bone-scraping affair.”

The woman’s skeleton led to an intriguing mystery. When her bones were closely examined scientifically, unusual details were noticed. According to writer Michael Price of Science Magazine, “Compared with other women at the Orthi Petra burial site, she was unusually muscular, especially on the right side of her body. She had also worn out the cartilage in her knee and hip joints, which would have made moving a painful, bone-scraping affair.”

When various experiments failed trying to discover what kinds of lifelong motions would have led to these results – clothes washing, bread baking, harvesting, loom weaving – the researchers turned to a neighbor. A master ceramicist’s daughter and potter who lived near the site agreed to model for the archaeologists. “Constantly flexing her leg to turn the kick wheel would have worn out her joints; repeatedly leaning to one side of the spinning clay to shape and sculpt it would have developed the muscles on that side of her body.” This means that the woman unearthed in the excavation site was “the only known female master ceramicist in the ancient Greek world,” (Archaeology) thereby breaking the male-dominated mold.

In addition, “four women related to one another and thought to have been priestesses were discovered in ornately furnished burials nearby.” Anthropologist Anagnostis Agelarakis of Adelphi University, who led the excavation team, noted the importance and privileged social position of women in Eleutherna. Studies showed that all four women and another dozen women discovered nearby shared a genetic dental trait, which is the reason archaeologists can say that they were all related. Historically, this era – between 900 BCE and 650 BCE, following the decline of the Minoan and Mycenean civilizations – is toward the end of what has been called the Greek Dark Ages, but the Eleutherna finds belie that assessment. According to Agelarakis, “these women were aristocratic. Their social standing was superlative.” Further, “their matrilineage was not ruptured for two centuries.”

In addition, “four women related to one another and thought to have been priestesses were discovered in ornately furnished burials nearby.” Anthropologist Anagnostis Agelarakis of Adelphi University, who led the excavation team, noted the importance and privileged social position of women in Eleutherna. Studies showed that all four women and another dozen women discovered nearby shared a genetic dental trait, which is the reason archaeologists can say that they were all related. Historically, this era – between 900 BCE and 650 BCE, following the decline of the Minoan and Mycenean civilizations – is toward the end of what has been called the Greek Dark Ages, but the Eleutherna finds belie that assessment. According to Agelarakis, “these women were aristocratic. Their social standing was superlative.” Further, “their matrilineage was not ruptured for two centuries.”

As we have seen before (Pompeii, women and St. Paul, Thecla, translation challenges), women of talent, significance and influence can be found in the literary and archaeological record from antiquity if one looks for it. It is the responsibility of the professionals in the fields who discover these traces of women to bring the evidence to light for the general public, and it is the responsibility of all of us to pay attention to these findings and apply their meaning to the lives of women and girls today.

Resources

Brown, Marley. “Breaking the Mold,” Archaeology, September/October 2018 (Vol. 71, No.5) 21.

Price, Michael. “Master female artisan broke the male-dominated mold in ancient Greece,” Science Magazine (Vol 361, Issue 6406), online at sciencemag.org, September 7, 2018