In several earlier posts, we have examined women who were leaders in the early Jesus movement – thus disproving the traditional argument of many Christian denominations that women could not (and therefore cannot) serve as leaders. ![]() We have shown how many anti-women assertions in the New (Christian) Testament of the Bible that have long been attributed to St. Paul were not actually written by him – because they were written after his death around 64 CE. From Paul’s circle, we have looked closely at the deacon Phoebe, the apostle Junia, missionary pairs Prisca/Priscilla and Aquila, Tryphaena and Tryphosa, Euodia and Syntyche, and other colleagues Persis and Julia. In addition, we have discussed Nympha from the letter to the Colossians and Mary Magdalene and several other women in Jesus’ circle.

We have shown how many anti-women assertions in the New (Christian) Testament of the Bible that have long been attributed to St. Paul were not actually written by him – because they were written after his death around 64 CE. From Paul’s circle, we have looked closely at the deacon Phoebe, the apostle Junia, missionary pairs Prisca/Priscilla and Aquila, Tryphaena and Tryphosa, Euodia and Syntyche, and other colleagues Persis and Julia. In addition, we have discussed Nympha from the letter to the Colossians and Mary Magdalene and several other women in Jesus’ circle.

We can know about these women because of scholarship – primarily by women – that has revealed new evidence from textual and archaeological sources and asked new questions of old evidence. This research moves the field forward – and even proves liberating for us today. Here we will delve into new research about Mary, the mother of Jesus – and the real possibility that she may have been viewed by some early Christian communities as a bishop.

Mary Traditions

Mary, Jesus’ mother, appears several times in the Christian Testament (Matt 1-2; 12:46-50, 13:55; Mark 3:31-35, 6:3; Luke 1:26-2:52, 8:19-21; John 2:1-12, 6:42, 19:25-27; Acts 1:14). It is important to note that the gospel accounts were written between 65 and 110 CE in different locations around the Mediterranean, 35-80 years after Jesus’ death. These relatively late gospel passages contain the stories about Mary about which we are familiar from the Christmas and crucifixion stories, plus the story of Jesus at age 12 teaching in the temple at Jerusalem.

Mary, Jesus’ mother, appears several times in the Christian Testament (Matt 1-2; 12:46-50, 13:55; Mark 3:31-35, 6:3; Luke 1:26-2:52, 8:19-21; John 2:1-12, 6:42, 19:25-27; Acts 1:14). It is important to note that the gospel accounts were written between 65 and 110 CE in different locations around the Mediterranean, 35-80 years after Jesus’ death. These relatively late gospel passages contain the stories about Mary about which we are familiar from the Christmas and crucifixion stories, plus the story of Jesus at age 12 teaching in the temple at Jerusalem.

In the gospel accounts, Mary has more children after Jesus (Matt 13:53-58, Mark 6:1-6, Acts 1:14) and witnesses Jesus’ crucifixion, but there is no account of Mary’s death. The last time we see Mary in the Christian Testament is in Acts 1:14, when she and the disciples are gathered in Jerusalem after Jesus’ death. Acts was written around 115 CE (Pervo, 214). Paul, our earliest source of information about the Jesus movement, does not mention Mary by name.

Therefore, the bulk of the information we have about Mary comes from extra-canonical (apocryphal) sources and later church doctrine. The main source of her familiar stories and legends as well as about Jesus’ youth come primarily from the Protevangelium of James (Infancy Gospel of James), written and circulated around 150 CE (Schaberg, 708-27). The Protevangelium and later works included stories about Mary’s mother and father and “pure birth” and the so-called “Dormition” tradition, her assumption into heaven. (See Abrahamsen, “Human and Divine,” especially 168-78, for a fuller discussion of Mary and her heritage.)

These stories became very popular over time in both the eastern and western branches of Christianity.  Significantly, according to scholar Raymond Brown (Mary in the New Testament, 253), “Most of the earliest patristic writings do not even mention Mary…. The only exception is in the letters of Ignatius, bishop of Antioch (A.D. 11-115). His five references to Mary provide not only an early witness to the belief in Jesus’ virginal conception but allow some inference about a polemical situation in which this theme must have played a role.” While some of the Mary stories may have been known fairly early on, most developed well after her earthly life.

Significantly, according to scholar Raymond Brown (Mary in the New Testament, 253), “Most of the earliest patristic writings do not even mention Mary…. The only exception is in the letters of Ignatius, bishop of Antioch (A.D. 11-115). His five references to Mary provide not only an early witness to the belief in Jesus’ virginal conception but allow some inference about a polemical situation in which this theme must have played a role.” While some of the Mary stories may have been known fairly early on, most developed well after her earthly life.

It is from the later years that Mary’s various titles and doctrines emerge: “Blessed Virgin Mary,” “Mother of God,” “Virgin Mary,” and “Theotokos”/“God-bearer” (“Mary, The Blessed Virgin,” Oxford, 882). It is important to note that Mary was viewed by different Christians in different ways down through the ages. While one “strand” may have portrayed her as the meek, obedient servant of God because she agreed to become Jesus’ mother, we can trace two additional strands: as a goddess in her own right, parallel to such Graeco-Roman deities as Isis, Ceres/Demeter (‘Mariolatry’, Oxford, 874) and Artemis (Wright and Neil, A Protestant Dictionary, 390) and, as we shall see, as a leader in the movement and perhaps even a bishop.

Jesus and Mary as a Pair

Long before the Graeco-Roman period, dating back thousands of years, people worshiped male and female deities. Evidence from the Neolithic era in Europe, the Middle East and elsewhere has been found showing that the very powerful nature goddess was often paired with a male counterpart (Abrahamsen, “Human and Divine,” 175). The male god was rarely depicted as a powerful king or ruler in his own right, since people knew that the role of the male – both human and animal – was secondary to and dependent upon that of the goddess. According to the late archaeologist Marija Gimbutas (Civilization, 249), “man’s sexual and physical power was esteemed as magically enhancing female life-giving powers. . . [I]t was believed that their fusing created potency necessary to charge nature with life powers.”

Since the Jesus movement emerged out of both Judaism and Graeco-Roman polytheism, a male-female pairing would not have been unusual. However, Jesus was not married (as far as we know), so another female figure was needed. There was a tradition of Mary Magdalene being a very close companion of Jesus, but it was Jesus’ mother who had become associated with miracles, as Jesus was: born to a pure couple, lived a holy life in a Jerusalem temple, impregnated in a miraculous way, purportedly retained her virginity throughout her life, and did not die. Therefore, some traditions began to pair Mary and Jesus in salvific ways.

Since the Jesus movement emerged out of both Judaism and Graeco-Roman polytheism, a male-female pairing would not have been unusual. However, Jesus was not married (as far as we know), so another female figure was needed. There was a tradition of Mary Magdalene being a very close companion of Jesus, but it was Jesus’ mother who had become associated with miracles, as Jesus was: born to a pure couple, lived a holy life in a Jerusalem temple, impregnated in a miraculous way, purportedly retained her virginity throughout her life, and did not die. Therefore, some traditions began to pair Mary and Jesus in salvific ways.

Ally Kateusz, Senior Research Associate at the Wijngaards Institute for Catholic Research in London, has amassed a sizable body of archaeological and artistic evidence for the pairing of Mary and Jesus in liturgical and other important settings. Much of this evidence has been hidden from view, or under-discussed by scholars, for centuries. Kateusz determined that, contrary to usual scholarly assumptions of longer narratives being embellished from earlier, more authentic, ones, the truth is the opposite: longer narratives were often shortened mainly for theological reasons by later scribes. These longer narratives are preserved in mosaics, paintings, and frescoes and on sarcophagi, crosses, and vessels – art tends to be more conservative than literature and thus remains longer in the record.

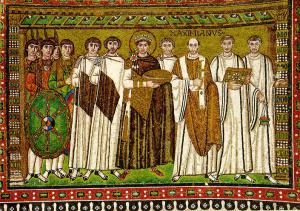

These examples contain many images of the pairing of Mary and Jesus in liturgical contexts. This is significant because of the church’s historic prohibition of women serving as priests. Kateusz’ research shows that, for centuries, contrary to what we have been taught, the church honored Mary, Jesus’ mother, as someone with authority – at least in conjunction with Jesus. In art examples from Rome, Constantinople, Ravenna, other Christian centers, and in both familiar and obscure manuscripts, the pairings signify Mary’s supreme importance for certain early Christians. Mary and Jesus are paired on silver flasks for holy oil, processional crosses, ivory book covers, and gold medallions that signify episcopal authority; that is, even at this relatively late date in the tradition (ca. 500-700 CE) Mary was seen as equal to Jesus.  In some examples, both figures are depicted on chalices – essential elements of the Eucharist (Communion, Mass) that only men came to be allowed to handle at the altar – or sitting on thrones (Kateusz, 103-11).

In some examples, both figures are depicted on chalices – essential elements of the Eucharist (Communion, Mass) that only men came to be allowed to handle at the altar – or sitting on thrones (Kateusz, 103-11).

Mary as Leader, Example and Bishop

Once we see that some branches of the church, over several centuries, depicted Mary and Jesus functioning together liturgically, we can then ask if there is even more specific evidence for Mary as a liturgical actor – a priest or even a bishop – in the record. If there is, today’s church must take note and examine its current practices of excluding women from leadership roles.

In Mary and Early Christian Women, Kateusz carefully examined the Six Book narrative, a tradition in many versions that describe Mary’s Dormition, or ascension into heaven. The “narrative depicts Jesus’s mother with considerable religious authority, including leading men in prayer as well as preaching” (Kateusz, 25). Further, the Six Books “associated Mary with the Temple priesthood” and “describes Mary using incense to make an offering” (ibid., 29). There are also stories of Mary giving other women small books, raising her hands in a priestly blessing, teaching women, sending out evangelists, and preaching – all actions depicting leadership and even priestly roles that became restricted to men (ibid., 43-44).

Going one vital step forward: if Mary was depicted in priestly and Eucharistic roles, what about the higher, more powerful bishop/overseer role? Kateusz has unearthed a number of examples:

- In the Euphrasiana Basilica in Croatia, a church dedicated to Mary that dates to the early sixth century, she was depicted twice in mosaics wearing the episcopal pallium, “the long white strip of cloth with a cross on it that was to be worn only when officiating at the Eucharist,” which later “became the distinctive episcopal symbol of the bishop’s vestment in the West” (Kateusz, 81, 82-84). (Interestingly, Mary’s cousin Elizabeth is also depicted on these mosaics – and wearing the pallium.)

Normally only male bishops would wear this piece of cloth.

Normally only male bishops would wear this piece of cloth. - In the Lateran Baptistery Chapel of San Venantius in Rome, dated to around 645, a mosaic of Mary was placed right over the altar. There were a number of men as well in this mosaic. “Mary herself wore an episcopal pallium with a red cross” and “red shoes,” both of which are still symbols of the Pope (Kateusz, 86).

- In Thessaloniki, the nave mosaic in Hagios Demetrios (ca. late 5th to 7th century) depicted Mary wearing a type of pallium (Kateusz, 87-88).

- A wall painting of Mary in the church of Maria Antiqua in Rome, ca. late 5th to 6th century, depicts her holding the white cloth that became known as the maniple, only worn by the priest during the Eucharist (Kateusz, 89-91).

- Relatedly, in the Commodilla Catacomb in Rome, “Mary is similarly painted holding the cloth in a mid-sixth-century wall painting” (Kateusz, 91).

In several of these examples, the baby Jesus is on Mary’s lap. “From the perspective of the laity in the nave, this mosaic portrait of Mary holding both her son and the fringed maniple created an inescapable visual analogy” (Kateusz, 93).

What, then, does all this say about women’s roles, if Mary (long after her death, of course) was viewed as a leader, even a bishop, herself? There definitely seems to be a connection. Using ancient texts and works of art from around the Mediterranean, Kateusz uncovers dozens of examples of women who led liturgies alone and alongside men and served in many communities as deacons, priests and bishops. Kateusz notes, “From the beginning in Christian communities, almost certainly women were associated with censers and incense [used in liturgies]. . . in Mediterranean culture women had the role of preparing and lamenting for the dead. . .” (Kateusz, 42). Further, Bishop Epiphanius around 370 reported that certain churches were ordaining women to the episcopate and priesthood, and some ancient documents such as the Didascalia Apostolorum discussed the roles of deacon and priest as equal between women and men (Kateusz, 153-54).

Conclusion

Why did Kateusz need to “discover” these examples? Why have they not come down to us in the history of the church and, indeed, the entire West?

Obviously (male) church leaders did not want this evidence preserved: “later scribes excised depictions of female leadership and authority that did not accord with the later Christian gender model” (Kateusz, 23).

We are grateful to Ally Kateusz for unearthing these amazing images of Mary as leader, priest and bishop.  It is doubtful that the actual mother of the earthly Jesus was such a leader (although that heritage may well have been erased in the manuscript tradition). However, the fact that some strands of Christianity – well into the Byzantine era – did honor her in these ways and was a model for real women to be leaders is not only inspiring but empowering.

It is doubtful that the actual mother of the earthly Jesus was such a leader (although that heritage may well have been erased in the manuscript tradition). However, the fact that some strands of Christianity – well into the Byzantine era – did honor her in these ways and was a model for real women to be leaders is not only inspiring but empowering.

If we are honest, we can no longer appeal to the authority of the early church and its leaders to deny women leadership roles, agency, influence, or power. Of course many of today’s Christians who do not support the leadership of women will appeal to that authority – will continue to try to suppress or criticize this evidence and to oppress or limit women. So, the question is, what will we do with the evidence and the truth?…

Resources

Abrahamsen, Valerie. “Human and Divine: The Marys in Early Christian Tradition,” in Amy-Jill Levine with Maria Mayo Robbins, eds., A Feminist Companion to Mariology, 164-81. London and New York: T & T Clark International, 2005.

Abrahamsen, Valerie. Review, Ally Kateusz, Mary and Early Christian Women: Hidden Leadership (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019), in The Fourth R, Vol. 36, No. 5 (Lehi, UT: Westar Institute, 2023) 25.

Brown, Raymond E., Karl P. Donfried, Joseph A. Fitzmyer, and John Reumann, eds. Mary in the New Testament. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1978.

Gimbutas, Marija. The Civilization of the Goddess, ed. Joan Marler. San Francisco: HarperSan Francisco, 1991.

Kateusz, Ally. Mary and Early Christian Women: Hidden Leadership. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

Kateusz, Ally, website

“Mariolatry,” in F.L. Cross and E.A. Livingstone, eds., Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 874. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

“Mary, The Blessed Virgin,” in F.L. Cross and E.A. Livingstone, eds., Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, 882-84. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

Pervo, Richard I. Dating Acts: Between the Evangelists and the Apologists. Santa Rosa: Polebridge Press, 2006.

Schaberg, Jane. ‘The Infancy of Mary of Nazareth,’ in Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, ed., Searching the Scriptures, Volume Two: A Feminist Commentary (New York: Crossroad, 1994), pp. 708-27.

Wright, Charles H.H. and Charles Neil, eds., A Protestant Dictionary, 390. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1904, as cited in http://www.islamic-awareness.org/Quran/Contrad/External/marytrin.html, January 2004.