The world is a serious place. When we examine the ancient world, especially as we look at the more serious (and even tragic) aspects of the history of the West, we are also confronted with images and concepts that normally do not make us smile, let alone laugh.

Here we will lighten things up a bit! There is a certain amount of humor, or at least light-heartedness, to be found when we examine our usual topics: Graeco-Roman society and religion, the early Jesus movement, and women in antiquity. We will also venture slightly into a later era, the Middle Ages. Enjoy!

Jesus Stories

Earlier, we looked at some stories about Jesus from extra-canonical literature. We saw how Christians in the second through sixth centuries of the Common Era (CE) took great liberty with tales they told about Jesus, especially as a baby and young boy.

A few apocryphal stories, as well as a few from the New (Christian) Testament, can make us smile even as they were told to demonstrate Jesus’ powers.

A few apocryphal stories, as well as a few from the New (Christian) Testament, can make us smile even as they were told to demonstrate Jesus’ powers.

- On the Holy Family’s flight to Egypt, Mary, Joseph and Jesus come to a cave where they hope to rest. They find it full of dragons! “Jesus subdues them and orders them to hurt no one” (The Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew 18; Cartlidge and Elliott, 101). One can imagine those hearing this story in the seventh or eighth century smiling, knowing full well that Mary, Joseph and Jesus would not have encountered dragons.

- Also on the flight to Egypt, the group encounters another cave, this one containing ferocious lions and panthers. The family’s donkey, on which Mary sits with Jesus at times, is depicted in a 15th-century manuscript illumination as looking “visibly perturbed.” The next image in the same text, however, shows the now-tamed beasts leading the ox and donkey – the latter now striding along confidently but with a “watchful eye on the crowd of predators before him” (Cartlidge and Elliott, 104).

- In a tale from the Arabic Infancy Gospel 13 (fifth or sixth century CE), the family “came to a place where there were robbers who had plundered many men of their baggage and clothes, and had bound them. Then the robbers heard a great noise, like the noise of a magnificent king going out of his city with his army, and his chariots and his drums; and at this robbers were terrified, and left all that they had stolen” (Cartlidge and Elliott, 104). The noise was Jesus’ approach. One can imagine hearers of the story cheering the robbers’ fear and fate.

- There are a number of stories that relate the young Jesus’ relationships with his teachers and how his questions and knowledge irritate his elders (Gospel of Thomas 14, 15, 19; Pseudo-Matthew 31). One particular illuminated manuscript even depicts an event where a teacher who disagrees with Jesus about a text dies! (But Jesus then raises him; Cartlidge and Elliott, 115). Many of us can remember, with some irritation, the one smart kid in middle school who was always asking the frustrated teacher, “will this be on the test?”

- Jesus (according to the Gospel of Matthew) took revenge on a fig tree! Matthew 21:18 (NRSV) reads: “In the morning, when he returned to the city, he was hungry. And seeing a fig tree by the side of the road, he went to it and found nothing at all on it but leaves. Then he said to it, ‘May no fruit ever come from you again!’ And the fig tree withered at once.”

Miscellaneous quotes

- Epicurus, who lived from 341 to 271 BCE, was “one of the most influential philosophers of the Hellenistic period. He founded his own philosophical school near Athens. Epicureans believed in ethical hedonism, whereby pleasure is the measure of what is good and pain is the measure of what is bad.” An epitaph from an Epicurean who did not believe in an afterlife captures the philosophy in one short phrase: “I was not, I was, I am not, I don’t care.”

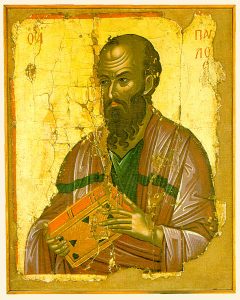

- St. Paul could apparently be a little boring at times, at least according to the author of Acts of the Apostles!

Acts 20:9-10 (NRSV) reads: “A young man named Eutychus, who was sitting in the window, began to sink off into a deep sleep while Paul talked still longer. Overcome by sleep, he fell to the ground three floors below and was picked up dead. But Paul went down, and bending over him took him in his arms, and said, ‘Do not be alarmed, for his life is in him.’”

Acts 20:9-10 (NRSV) reads: “A young man named Eutychus, who was sitting in the window, began to sink off into a deep sleep while Paul talked still longer. Overcome by sleep, he fell to the ground three floors below and was picked up dead. But Paul went down, and bending over him took him in his arms, and said, ‘Do not be alarmed, for his life is in him.’” - The story of Pentecost in Acts 2, known as the “birthday of the church,” is read in congregations 50 days after Easter and usually gets a good laugh. Here’s the punchline: “Others sneered and said, ‘They are filled with new wine.’ But Peter, standing with the eleven, raised his voice and addressed them, ‘Men of Judea and all who live in Jerusalem, let this be known to you, and listen to what I say. Indeed, these are not drunk, as you suppose, for it is only nine o’clock in the morning.”

“Uppity women” stories

Vicki León has given us a real gift with Uppity Women of Medieval Times. While the women she portrays often lived difficult (or even naughty) lives, León’s story-telling skills expertly bring out the lighter aspects of these women’s lives. Here are a few examples.

Parnell Portjoie. “If you were headed for the Bankside district of London around 1290, you could only be looking for one thing: sexual healing and dealing. Bankside brothels were famous – and none more so than the establishment of Parnell Portjoie, whose ‘door of joy’ was open to all. She and her pimp, Nicholas Pluckrose, … ran this busy love nest for an absentee owner.  Its profits were a Godsend – or maybe that was just inside pull. As the municipal records still show, the behind-the-scenes boss happened to be a local bishop of the Church of England” (León, 97).

Its profits were a Godsend – or maybe that was just inside pull. As the municipal records still show, the behind-the-scenes boss happened to be a local bishop of the Church of England” (León, 97).

Maria Victoria della Verde. “Goodness knows, you could never do too much praying, rosary-counting, and genuflecting in a sixteenth-century Italian nunnery. Nevertheless, a nun by the name of Maria Victoria della Verde found time on her hands. What to do? Maria and her advisors being Italian, the answer was: cook. Maybe even throw together a publication of, say, nice recipes from the nunnery. In the late 1500s, Maria embarked on her culinary quest. No wimpy little ecclesiastical foods in this collection: Besides pasta, pasta, pasta, she included that old favorite among women in religious orders, strozzapretti. A recipe for caloric, cholesterolic dumplings, strozzapretti translates as ‘priest strangler.’ An in-joke among nuns – or wishful thinking from the distaff religious population? Maria left no answer to this, one of history’s minor mysteries” (León, 171).

Caterina da Vinci. “Caterina had three problems.  She was poor; she was pregnant; and she was pretty darned sure that a certain fast-talking legal-beagle from Florence wasn’t going to pop the question. She had a child in 1452 – and then got in Mr. One-Night-Stand’s face, so he agreed to adopt his illegitimate new son and educate him. Despite Caterina’s absence from the scene as a mom, the kid turned out pretty well. His teachers said, ‘Lacks focus, but boy! can he draw….’ Eventually Leonardo was receiving coveted art commissions from kings, popes, and other despots with extra lira – although, frankly, he would just as soon have kept messing around with futuristic ideas for mechanical devices and making weird paint experiments. By the twentieth century, little old Caterina’s boy, born in the hick village of Vinci, was recognized as one of the greatest geniuses of all time” (León, 64).

She was poor; she was pregnant; and she was pretty darned sure that a certain fast-talking legal-beagle from Florence wasn’t going to pop the question. She had a child in 1452 – and then got in Mr. One-Night-Stand’s face, so he agreed to adopt his illegitimate new son and educate him. Despite Caterina’s absence from the scene as a mom, the kid turned out pretty well. His teachers said, ‘Lacks focus, but boy! can he draw….’ Eventually Leonardo was receiving coveted art commissions from kings, popes, and other despots with extra lira – although, frankly, he would just as soon have kept messing around with futuristic ideas for mechanical devices and making weird paint experiments. By the twentieth century, little old Caterina’s boy, born in the hick village of Vinci, was recognized as one of the greatest geniuses of all time” (León, 64).

Eva Giffard. “In the middle of the thirteenth century, the port town of Waterford, Ireland, was shamrock green, covered with sheep, and a terrible place to make a living. A local weaver and wool saleswoman, Eva Giffard couldn’t seem to get ahead… Then it came to her – why not cut out the middleperson in the sheep racket? Accordingly, she identified a particularly fluffy group of animals and paid them a visit one night…. [She] rolled up her sleeves and ripped the wool right off the backs of twenty dazed sheep with her bare hands. Someone bleated, however. Eva was busted before she even got to page two of her business plan. Brought before a judge, Eva spun an excellent yarn and was almost set free, when an alert official thought to check her priors. Holy Saint Bridget! Turns out this wasn’t the first time the law-abiding citizens – and sheep – of Waterford had been fleeced by this feminine bit of blarney. Make that a ewe-turn for Eva” (León, 13).

Resources

Cartlidge, David R. and J. Keith Elliott. Art and the Christian Apocrypha. London and New York: Routledge, 2001.

León, Vicki. Uppity Women of Medieval Times. New York: MJF Books, 1997.