There are movements afoot in our country – by those on the political right, including many elected officials at all levels of government – to reverse social, racial and economic progress that most Americans acknowledge has been made over the past 40-50 years. “Progress,” however, is not how those Americans on the right characterize certain trends. They argue that “progressive” movements such as affirmative action, the removal of Lost Cause statues from towns across the nation, abortion access, critical race theory (which is not taught in public schools, as the right alleges), gender reassignment procedures, and presumed “discrimination” against Christianity are not progress but rather dangerous trends that irreparably harm society and corrupt our children. These critics on the right – such as Florida Governor Rick DeSantis – would rather have the US return to a time when someone in his demographic – straight, white, male and “Christian” of a certain bent – held nearly all the power and financial resources.

Those of us who applaud most social progress initiatives – efforts and legislation that attempt to create a society that is fair and equitable for everyone – must try hard in this fraught time to continue taking steps forward. In this, Black History Month, we can educate ourselves about the African American experience, even from the comforts of our homes.  We can also applaud steps that are being taken to right painful, unforgivable wrongs. More can and should always be done along these lines – but taking first steps, no matter how small – are a constructive beginning.

We can also applaud steps that are being taken to right painful, unforgivable wrongs. More can and should always be done along these lines – but taking first steps, no matter how small – are a constructive beginning.

Resources

Several renowned museums and nonprofit organizations are launching online programs for our edification.

Matthew F. Delmont, professor of history at Dartmouth College, has established Black Quotidian: Everyday History in African-American Newspapers as a free online resource.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, DC, was established by an Act of Congress in 2003 and opened to the public on September 24, 2016. The Museum promotes and highlights the contributions of African Americans, which enhance the understanding of our country’s history for all of us. The Museum is offering a number of online programs to celebrate Black History Month.

The National Cathedral in Washington – technically, the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul – is an American cathedral of the Episcopal Church but also serves as “A House of Prayer for All People.” Americans might be most familiar with the Cathedral as the setting for the funerals of our Presidents and other dignitaries. In addition to its usual worship and musical offerings, the Cathedral has several offerings in honor of Black History Month.

The National Cathedral in Washington – technically, the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter and Saint Paul – is an American cathedral of the Episcopal Church but also serves as “A House of Prayer for All People.” Americans might be most familiar with the Cathedral as the setting for the funerals of our Presidents and other dignitaries. In addition to its usual worship and musical offerings, the Cathedral has several offerings in honor of Black History Month.

For people living in or visiting Boston or Nantucket, The Museum of African American History Boston-Nantucket “connects colonial and early African American history & culture in Boston and the larger New England area with the abolition of slavery and current explorations of race and the struggle for human rights.” It “is nationally and internationally known for its collection of historic sites in Boston and Nantucket, including two African Meeting Houses Abiel Smith School, Seneca Boston- Florence Higginbotham House, Black Heritage Trails®.”

Renaming of US Forts and Bases

It has become clear to Americans over the past several years that many of our military bases have been named after – and have thus significantly honored – Confederate generals who actually worked to destroy the Union in the Civil War. In 2021, Congress established the Commission on the Naming of Items as part of the National Defense Authorization Act. In October 2022, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin approved the Commission’s recommendations, and the Defense Department has begun to implement the commission’s recommendations as mandated by the law.  According to CBS News, renaming ceremonies will take place during this time, and the process must be completed by the end of 2023.

According to CBS News, renaming ceremonies will take place during this time, and the process must be completed by the end of 2023.

- Fort Benning in Georgia is expected to be renamed Fort Moore “in commemoration of Lieutenant General Hal Moore, a famed cavalry officer depicted in [the film] ‘We Were Soldiers,’ and his wife, Julia Moore, who spurred the Army to create casualty notification teams,” according to Military.com and as reported in Daily Kos, October 14, 2022. This Fort was named after Confederate Army Brigadier General Henry L. Benning (1814-1875), who served on the Georgia State Supreme Court, was an outspoken advocate of secession (in order to preserve slavery), and led Confederate troops in battles in Virginia.

- The Commission recommends that Fort Polk, Louisiana, be renamed Fort Johnson after Sergeant William Henry Johnson, “a Black Medal of Honor recipient for valor during World War I,” per Military.com. To the shame of the Episcopal Church, Fort Polk was named after Leonidas Polk (1806-1864), who started at West Point but had a conversion experience and became a priest and eventually a Bishop in the Protestant Episcopal Church (Louisiana, 1841). Polk, who had acquired slaves through his marriage, attempted to live a somewhat benevolent life and used his energy and skills to raise funds and acquire land toward what ultimately became Sewanee: The University of the South at Sewanee, Tennessee. The University was an Episcopal institution “dedicated to training Southern aristocrats in their responsibilities toward blacks” (although today its mission is EQB, for “Ecce Quam Bonum,” taken from Psalm 133 for “how good and pleasant it is when kindred live together in unity”). Despite these admirable initiatives, Polk reluctantly accepted a commission as major general in the Confederate Army as the Civil War commenced. He was assigned the job of defending the Mississippi River and defeated Ulysses S. Grant’s troops at Belmont, Missouri, in November 1861. Polk also led four charges at Shiloh, Tennessee, and, in October 1862, was promoted to lieutenant general. At Pine Mountain, Georgia, in June 1864, he was fatally wounded.

- The Commission recommends that Fort Bragg in North Carolina be renamed Fort Liberty after the value of liberty.

Fort Bragg was originally named after Confederate General Braxton Bragg (1817-1876), who saw Civil War battle – several times very successfully against Union forces – in Kentucky and especially Tennessee. Despite being censured for his unwillingness to fight to a decision at the Battle of Perryville, Kentucky, Bragg came into favor with Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who named Bragg his military adviser. Bragg worked as a civil engineer after the War.

Fort Bragg was originally named after Confederate General Braxton Bragg (1817-1876), who saw Civil War battle – several times very successfully against Union forces – in Kentucky and especially Tennessee. Despite being censured for his unwillingness to fight to a decision at the Battle of Perryville, Kentucky, Bragg came into favor with Confederate President Jefferson Davis, who named Bragg his military adviser. Bragg worked as a civil engineer after the War.

Additional recommendations – three in Virginia and one each in Georgia, Texas and Alabama – shed further light on why these name changes are necessary in order to promote the values of equality, racial harmony, and respect for women.

- Fort A.P. Hill, Virginia: rename it Fort Walker after Dr. Mary Walker. A.P. Hill was Ambrose P. Hill (1825-1865), a native of Culpeper, Virginia, and a graduate of West Point. He was a highly-regarded general during the Civil War but, in the end, “proclaimed that he had no desire to see the end of the Confederacy,” rode to the front lines at the Third Battle of Petersburg, and was shot dead, just days before Lee’s surrender. Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, by contrast (1832-1919), should be considered a true American hero. She is the only woman ever to receive the Medal of Honor, for her service during the Civil War, first as an unpaid surgeon (because the Union Army denied her a commission as a medical officer) on the front lines at Fredericksburg and Chattanooga, then as a civilian surgeon with the 52nd Ohio Infantry.

At one point she was arrested by Confederate troops for spying, was imprisoned for four months at a notorious prison near Richmond, Virginia, and was freed in a prisoner exchange. “During the remainder of the war, she served at the Louisville Women’s Prison Hospital and at an orphan asylum in Clarksville, Tennessee,” according to the National Park Service. Because she wore men’s clothing throughout her life, she suffered harassment and ridicule. In her later years she was active in the women’s suffrage movement and “opened her home to those who were also ostracized, harassed, and arrested for not conforming to traditional ideas of how people should dress.”

At one point she was arrested by Confederate troops for spying, was imprisoned for four months at a notorious prison near Richmond, Virginia, and was freed in a prisoner exchange. “During the remainder of the war, she served at the Louisville Women’s Prison Hospital and at an orphan asylum in Clarksville, Tennessee,” according to the National Park Service. Because she wore men’s clothing throughout her life, she suffered harassment and ridicule. In her later years she was active in the women’s suffrage movement and “opened her home to those who were also ostracized, harassed, and arrested for not conforming to traditional ideas of how people should dress.” - Fort Lee, Virginia: rename it Fort Gregg-Adams after Lieutenant General Arthur Gregg and Lieutenant Colonel Charity Adams. Fort Lee was originally named after the commanding General of the Confederacy, Robert E. Lee, but is being renamed after two accomplished African Americans. Arthur Gregg served Fort Lee for 35 years and retired as the second-highest ranked black officer at the time in 1981; he was serving as deputy director of logistics for the entire Army. Charity Adams joined the Army in 1942 and rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel (the highest rank for a woman service member at the time). Adams was the first African American woman in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps and commander of the first World War II battalion with black women as its only members. Adams headed the 6888th Central Postal Directory in England, the department responsible for delivering mail to and from the several million soldiers fighting in Europe during World War II. Adams died in 2002.

- Rename Fort Pickett in Virginia Fort Barfoot after Technical Sergeant Van T. Barfoot.

While General George Pickett (1825-75) was a distinguished Major General on the Confederate side of the Civil War, despite his personal dislike of slavery, Van T. Barfoot received the Medal of Honor for his actions with the 45th Infantry Division in Italy in 1944. In courageous efforts over and above the call of duty, Barfoot saved several of his fellow soldiers under fire and took 17 prisoners, in addition to killing and wounding a number of enemy combatants.

While General George Pickett (1825-75) was a distinguished Major General on the Confederate side of the Civil War, despite his personal dislike of slavery, Van T. Barfoot received the Medal of Honor for his actions with the 45th Infantry Division in Italy in 1944. In courageous efforts over and above the call of duty, Barfoot saved several of his fellow soldiers under fire and took 17 prisoners, in addition to killing and wounding a number of enemy combatants. - Fort Gordon, Georgia: rename it Fort Eisenhower after General of the Army Dwight Eisenhower. Eisenhower, of course, is or should be very well known to Americans, especially as our 34th President. John Brown Gordon (1832-1904), however, should be acknowledged for what he was: a Confederate lieutenant general, an opponent of Reconstruction, and a rumored Grand Dragon in the Ku Klux Klan. While Gordon helped steer the New South in the direction of commercialism and industrialism when the War ended, he became commander in chief of the newly-formed United Confederate Veterans organization in 1890 and served in the position until his death.

- Rename Fort Hood in Texas Fort Cavazos after General Richard Cavazos. John Bell Hood (1831-79) is yet another example of a Confederate General after whom one of our Forts has been named. Hood, who hailed from Kentucky, rose quickly in the Confederate Army ranks and saw service in many battles against Union forces. On the other hand, Mexican American and Texas native Richard E. Cavazos, who was a hero in both the Korean and Vietnam Wars, made military history in 1976 when he became the first Hispanic to attain the Army rank of brigadier general. He made history again, in 1982, by being appointed the Army’s first Hispanic four-star general.

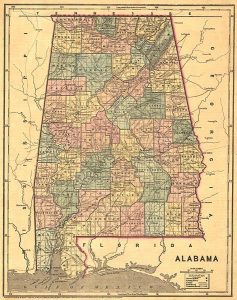

- Fort Rucker, Alabama: rename it Fort Novosel after Chief Warrant Officer 4 Michael J. Novosel, Sr. According to the Department of Defense, Novosel “was an aviator who flew combat in both World War II and Vietnam and received the Medal of Honor for a Medevac mission under fire in Vietnam where he saved 29 soldiers.” In contrast, Edmund Winchester Rucker (1835-1924) was another Confederate officer – although his rank of General was only honorary.

He worked in the railroad business before the Civil War then returned to that arena after leading troops in a number of battles. His loyalty to the southern cause never wavered after the War: he worked with the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, General Nathan Bedford Forest (who had earlier arranged a prisoner exchange for him), and with another Confederate General, Joseph E. Johnston, in business. Rucker’s southern sympathies were honored by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which named Chapter 2534 after him.

He worked in the railroad business before the Civil War then returned to that arena after leading troops in a number of battles. His loyalty to the southern cause never wavered after the War: he worked with the first Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan, General Nathan Bedford Forest (who had earlier arranged a prisoner exchange for him), and with another Confederate General, Joseph E. Johnston, in business. Rucker’s southern sympathies were honored by the United Daughters of the Confederacy, which named Chapter 2534 after him.

There is a disturbing and shameful pattern connected to the original naming of these Forts. As the Department of Defense itself now acknowledges, “Some Army bases, established in the build-up and during World War I, were named for Confederate officers in an effort to court support from local populations in the South. That the men for whom the bases were named had taken up arms against the government they had sworn to defend was seen by some as a sign of reconciliation between the North and South. It was also the height of the Jim Crow Laws in the South, so there was no consideration for the feelings of African Americans who had to serve at bases named after men who fought to defend slavery.”

Those of us who are white Americans have a particular responsibility to constantly educate ourselves about the whole of our history, not only those parts that are comfortable and positive. We do this not to feel guilty but to keep growing ourselves, to help create “a more perfect union” and to contribute to the common good. Let all of us joyfully celebrate Black History Month!

As we celebrate Black History Month, there is no denying that there are inequalities in our country that need addressing. Closing the racial wealth gap in America isn’t a simple fix, but many experts say education and financial literacy can help. To shed light on the topic, we’ve created an in-depth article discussing:

– The impact that this knowledge gap has on the African American community

– Socioeconomic and cultural barriers

– The role of Black financial advisors

Jullieth Cragwell, Outreach Coordinator, Annuity.org

https://annuity.org/financial-literacy/black-community/