We have examined the legacy of St. Paul and his letters to the early Christian communities several times in the past. We have noted that one of the ways that Paul communicated with original Jesus followers in the first century was through his letters (epistles) and that a number of letters in the New (Christian) Testament traditionally attributed to Paul were not written by him but rather by others after his death. ![]() Here we will examine in a little more detail how scholars determine which letters are authentic, which are not, and why it matters; we will focus on passages in some of the inauthentic letters known as the “household codes.”

Here we will examine in a little more detail how scholars determine which letters are authentic, which are not, and why it matters; we will focus on passages in some of the inauthentic letters known as the “household codes.”

The Manuscript Evidence

Over the past 150 years, scholars with various types of expertise have analyzed the manuscripts of the Christian Testament, where Paul’s letters are found, in their original languages and in relationship to other ancient literature of the first few centuries. The manuscripts, which now “live” in museums and libraries throughout the world, number in the thousands, are in various levels of completeness, readability and physical condition, often bear marginal “editorial” notes by the scribes who copied them (usually in monasteries and convents), and frequently demonstrate discrepancies.

Consequently, this type of scholarly analysis can determine with some degree of accuracy when ancient letters and other documents were written and circulated, where they may have originated, how they were received, and when they may have been recognized by the larger church as authoritative. Since Paul most likely visited and/or wrote to the early congregations between 50 and 60 of the Common Era (CE) and died in Rome between 62 and 64, we can conclude that any letters that are proven, by evidence, to have only circulated after 62-64 were not written by him.

Based on these criteria, the letters that most scholars agree were written or dictated by Paul were Romans, I Corinthians, II Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, I Thessalonians, and Philemon.

It can be confusing in church and other settings (including college classes) that other letters that are often attributed to Paul – Ephesians, Colossians, II Thessalonians, I Timothy, II Timothy, Titus and sometimes Hebrews – were most likely not.  The Christian church over time, and nowadays especially its Fundamentalist “wing,” generally argues for Pauline authorship, and it can be these traditional views that are picked up most readily in an internet search and public discourse.

The Christian church over time, and nowadays especially its Fundamentalist “wing,” generally argues for Pauline authorship, and it can be these traditional views that are picked up most readily in an internet search and public discourse.

What difference does it make whether Paul wrote these epistles or not? After all, some of the sentiments in the non-Pauline letters are important, worthy of respect and even beautiful.

Many scholars of the Christian Testament and early church history maintain that, yes, authenticity does matter. Paul’s words have had and continue to have a great deal of influence on Western civilization due to his stature in the church over the past two millennia and the church’s influence on the West. When words are put in Paul’s mouth that should not be there – and when words are not there that should be – all of us are impoverished.

One of the most significant ways in which Paul has shaped our culture is women’s roles in church and society. We have already explored Paul’s views of women by examining women whom Paul knew personally and who had leadership roles in the early congregations (Rome, Philippi; and Corinth).  We have shown how, if women leaders in Paul’s communities (and subsequently in his letters) had been held in higher regard by the growing church rather than oppressed and silenced, church and society would be vastly different – and perhaps significantly better.

We have shown how, if women leaders in Paul’s communities (and subsequently in his letters) had been held in higher regard by the growing church rather than oppressed and silenced, church and society would be vastly different – and perhaps significantly better.

Here we will look at another aspect of the authenticity-inauthenticity question: that of the so-called “household codes.” An examination of these codes will demonstrate that they appear only in the non-Pauline letters but, in a very short period of time in the early Christian era, reversed the respect that Paul had apparently shown toward the women in his circles. These passages have also negated other visions of equality found in Paul’s authentic letters and other portions of Christian tradition. The church, arguing that Paul had promoted oppressive beliefs and practices when he most likely had not, caused the church – and society – to devolve into a hierarchical and regimented system that has adversely affected us ever since.

The Household Codes

The household codes are ancient formulations depicting “relationships of the male head of household with his wife, children, and slaves – an integral part of the affluent household in Roman society. . . .These descriptions assume a social world in which dominant males control all women, children, and other men, in which women are essentially inferior to men, and in which slavery is pervasive and seldom questioned.”

The household codes are found in various configurations in the following Christian Testament texts: Colossians 3:18-4:1; Ephesians 5:22-6:9; I Timothy 5:1-6:2; Titus 2:2-10; and I Peter 3:1-7. All of these passages except that from I Peter have traditionally been attributed to Paul (and I Peter is attributed to St. Peter but almost certainly not written by him). While there is some scholarly debate about the date of Colossians, it is most closely related to Ephesians, which can be firmly dated to after Paul’s death. Here are the dates that scholars surmise about these epistles’ writing/circulation:

- Colossians (50-80 CE)

- Ephesians (80-100 CE)

- I Peter (80-110 CE)

- I Timothy (100-150 CE)

- Titus (100-150 CE)

These epistles were written at a time that the new “Christ cult” had branched off from Judaism following the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE. This was a time in which Jews needed to regroup and non-Jews (pagans who had followed the traditional deities of the ancient world) were being drawn into the Jesus movement. Thus the theological and practical points being made in later epistles to the Christian groups throughout the Empire were of necessity different than the messages promulgated by Paul.

This patriarchal nature of the household in the wider Roman world – with its superior/subordinate hierarchy – carried over into the early church, since the earliest communities of Jesus followers met in private homes. While Paul was not totally immune to this structure – his authentic letters do betray a certain ambiguity toward women’s roles (I Corinthians 11:2-16 and 14:34-35), and he cannot completely condemn human slavery (see his letter to Philemon) – his primary “code” is found in Galatians 3:28, which can be dated to the 50s CE: “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus” (NRS).

This patriarchal nature of the household in the wider Roman world – with its superior/subordinate hierarchy – carried over into the early church, since the earliest communities of Jesus followers met in private homes. While Paul was not totally immune to this structure – his authentic letters do betray a certain ambiguity toward women’s roles (I Corinthians 11:2-16 and 14:34-35), and he cannot completely condemn human slavery (see his letter to Philemon) – his primary “code” is found in Galatians 3:28, which can be dated to the 50s CE: “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus” (NRS).

The later, non-Pauline writings, in contrast, betray the concern the emerging church had for preserving hierarchical norms.

- The author of Colossians quotes Gal. 3:28 but, according to noted NT scholar Elisabeth Schüssler Fiorenza, changes it considerably. The Colossians household code is “the first and most precise form of the domestic code in the New Testament” (Schüssler Fiorenza, 253). Scholar Sarah Tanzer notes that the author exhorts each party of the pairs listed – wives/husbands, children/parents and slaves/masters – to behave appropriately toward each other. These relationships are meant, in Colossians, to reflect the universal lordship of Christ, and this theme “endorses social patterns of restricting and subordinating women, children, and slaves” (Tanzer, 484-85).

- Of importance to the author of Ephesians is unity and reconciliation within the Jesus communities, along with the obligation of subordinate persons to behave appropriately toward their superiors.

Wives are exhorted to “be subject” to their husbands, yet “[t]here is no parallel consistency in the verbs used to exhort husbands” (Tanzer 482). The codes in general “idealize the Christian household as a hierarchically ordered social unity . . . [and] the self-understanding of the church as an interdependent household in relationship to Christ” (Tanzer, 481).

Wives are exhorted to “be subject” to their husbands, yet “[t]here is no parallel consistency in the verbs used to exhort husbands” (Tanzer 482). The codes in general “idealize the Christian household as a hierarchically ordered social unity . . . [and] the self-understanding of the church as an interdependent household in relationship to Christ” (Tanzer, 481). - The emphasis for the pseudo-Pauline author of I Timothy in the household code is to give instructions to “three problematic groups within the church: widows, elders, and slaves” (Tanzer, 492). By this time in the church’s development, it has become important “to protect and foster the true teachings of the [church] tradition” and “combat the proclamation of other teachings” (Schüssler Fiorenza, 288). The communities reflected in the so-called Pastoral Epistles (I and II Timothy and Titus) are now more stratified, and we begin to see structures that will become more “set in stone” as time goes on:

the overseer/bishop (parallel to the traditional paterfamilias), presbyters/priests (both male and female), and deacons (both male and female). The “natural” order of age (older over younger) and gender (male over female) are still preserved, as is the supremacy of elites and the wealthy over others: women can serve the church but cannot teach or have authority over men, which thus prohibits them from ever serving as bishop (Schüssler Fiorenza, 288-90). Given the relationships Paul actually had with women, as we’ve noted, it is hard to imagine him really saying what is recorded in I Tim 14-15: “So I would have younger widows marry, bear children, and manage their households, so as to give the adversary no occasion to revile us. For some have already turned away to follow Satan” (NRS).

the overseer/bishop (parallel to the traditional paterfamilias), presbyters/priests (both male and female), and deacons (both male and female). The “natural” order of age (older over younger) and gender (male over female) are still preserved, as is the supremacy of elites and the wealthy over others: women can serve the church but cannot teach or have authority over men, which thus prohibits them from ever serving as bishop (Schüssler Fiorenza, 288-90). Given the relationships Paul actually had with women, as we’ve noted, it is hard to imagine him really saying what is recorded in I Tim 14-15: “So I would have younger widows marry, bear children, and manage their households, so as to give the adversary no occasion to revile us. For some have already turned away to follow Satan” (NRS). - The household code in Titus, also attributed to Paul, long dead, is meant in part to ensure that the wider society holds a good opinion of the church; this the author does by encouraging “conformity to social norms and submission to appropriate authorities” (Tanzer, 495). This stance is quite a change from the possible equality between church members as envisioned by Paul and others in the early movement. Rather, the author of Titus warns against women “teaching beyond the domestic sphere; … following Christian ascetic tendencies and upsetting the family household; … [and] asserting their leadership” (Tanzer, 495).

- Finally, the author of I Peter, writing in the name of one of Jesus’ earliest followers who, according to legend, became the first Pope, presents an incomplete version of the household code that addresses only servants, wives and husbands; the children/parents pair is missing. The context of the letter is the hostile environment for Christians in Asia Minor, so a major purpose of the letter is to comfort and encourage these believers in the faith – in part by appealing to the advantage of traditional mores and structures. The letter’s message includes equating the innocent suffering of these church members with the “silent and noble suffering of Jesus.” Sadly, because this letter is authoritative in the churches, “the believer is presented with a lofty justification for victimization, violence, and abuse” (Tanzer 498).

Conclusion

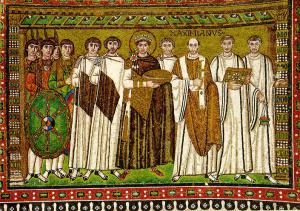

The household codes that appear in the Christian Testament demonstrate how important it is to distinguish between the authentic and inauthentic writings of St. Paul. The codes have been passed down in Christian tradition for two millennia, with (primarily male) church officials insisting that the hierarchical exhortations primarily to women are “the will of God,” since they purportedly came from the inspired “pen” of the church’s founder.  Male leaders, husbands and fathers in the church context have been granted nearly unlimited authority over not only women but also other men and non-elites; because the church has been so powerful and influential in the West since the time of the Emperor Constantine (313 CE), this oppression has been the tragic reality outside the church as well.

Male leaders, husbands and fathers in the church context have been granted nearly unlimited authority over not only women but also other men and non-elites; because the church has been so powerful and influential in the West since the time of the Emperor Constantine (313 CE), this oppression has been the tragic reality outside the church as well.

How might things in our culture have been different had the real Paul – that Paul who praised and honored Priscilla, Chloe, Apphia, Phoebe, Mary, Junia, Tryphaena, Tryphosa, Euodia, Syntyche, Rufus’ mother, Julia, and Nereus’ sister – been highlighted in the churches rather than silenced throughout history? Today, by recognizing these named women AND by learning more about early Christian literature and its biases we have better tools to promote justice and equality in church and society.

Resources

Kirby, Peter. “The Early Christian Writings: New Testament, Apocrypha, Gnostics, Church Fathers,” http://earlychristianwritings.com/.

Kraemer, Ross. S. “Mother (and Father) to Be Honored,” in Carol Meyers, Toni Craven and Ross S. Kraemer, eds., Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, and the New Testament, 483. Grand Rapids, MI, and Cambridge, England: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2000.

Kraemer, Ross. S. “Women (and Men) Slave Owners,” in Carol Meyers, Toni Craven and Ross S. Kraemer, eds., Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, and the New Testament, 483-84. Grand Rapids, MI, and Cambridge, England: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2000.

Meyers, Carol, Toni Craven and Ross S. Kraemer, eds. Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, and the New Testament. Grand Rapids, MI, and Cambridge, England: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2000.

Osiek, Carolyn. “Household Codes,” https://www.bibleodyssey.org/en/people/related-articles/household-codes.

Schüssler Fiorenza, Elisabeth. In Memory of Her. New York: Crossroad Publishing Co., 1983.

Tanzer, Sarah J. “Older and Younger Women,” in Carol Meyers, Toni Craven and Ross S. Kraemer, eds., Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, and the New Testament, 491-92. Grand Rapids, MI, and Cambridge, England: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2000.

Tanzer, Sarah J. “Older and Younger Women Exhorted,” in Carol Meyers, Toni Craven and Ross S. Kraemer, eds., Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, and the New Testament, 494-95. Grand Rapids, MI, and Cambridge, England: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2000.

Tanzer, Sarah J. “Wives (and Husbands) Exhorted,” in Carol Meyers, Toni Craven and Ross S. Kraemer, eds., Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, and the New Testament, 480-82. Grand Rapids, MI, and Cambridge, England: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2000.

Tanzer, Sarah J. “Wives (and Husbands) Exhorted,” in Carol Meyers, Toni Craven and Ross S. Kraemer, eds., Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, and the New Testament, 484-85. Grand Rapids, MI, and Cambridge, England: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2000.

Tanzer, Sarah J. “Wives (and Husbands) Exhorted,” in Carol Meyers, Toni Craven and Ross S. Kraemer, eds., Women in Scripture: A Dictionary of Named and Unnamed Women in the Hebrew Bible, the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books, and the New Testament, 497-99. Grand Rapids, MI, and Cambridge, England: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2000.