The mission of the Archaeological Institute of America reads, in part, “The AIA promotes archaeological inquiry and public understanding of the material record of the human past to foster an appreciation of diverse cultures and our shared humanity.” The values of the Archaeological Conservancy, as stated on their website, include the following: “The Archaeological Conservancy is the only national, nonprofit organization that identifies, acquires, and preserves the most significant archaeological sites in the United States…. When ancestral Native American villages are damaged and destroyed by looters or leveled for shopping centers, it lessens us as Americans.” A stated commitment of the Penn Museum is, “We commit to embracing and applying a DEIA (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility) mindset in everything we do with and for our entire community, including staff, research and community partners, and the public we serve.” In addition, “The Penn Museum respectfully acknowledges that it is situated on Lenapehoking, the ancestral and spiritual homeland of the Unami Lenape.”

The mission of the Archaeological Institute of America reads, in part, “The AIA promotes archaeological inquiry and public understanding of the material record of the human past to foster an appreciation of diverse cultures and our shared humanity.” The values of the Archaeological Conservancy, as stated on their website, include the following: “The Archaeological Conservancy is the only national, nonprofit organization that identifies, acquires, and preserves the most significant archaeological sites in the United States…. When ancestral Native American villages are damaged and destroyed by looters or leveled for shopping centers, it lessens us as Americans.” A stated commitment of the Penn Museum is, “We commit to embracing and applying a DEIA (Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Accessibility) mindset in everything we do with and for our entire community, including staff, research and community partners, and the public we serve.” In addition, “The Penn Museum respectfully acknowledges that it is situated on Lenapehoking, the ancestral and spiritual homeland of the Unami Lenape.”

The common thread among these three major organizations devoted to archaeological research is that today they are consciously devoted to linking their archaeological expertise with social justice goals and the stories and values of underrepresented peoples.  It is not always easy for universities and other entities that support archaeological excavations or for cash-strapped museums to mount exhibits that might at first not be attractive to donors and Board members. As we shall see, however, the attempts must be made – and the results are often beneficial not only to the institutions themselves but also to our wider world.

It is not always easy for universities and other entities that support archaeological excavations or for cash-strapped museums to mount exhibits that might at first not be attractive to donors and Board members. As we shall see, however, the attempts must be made – and the results are often beneficial not only to the institutions themselves but also to our wider world.

Here are some exciting examples of recent discoveries in archaeology that show a commitment to telling stories of a wide range of human beings and the importance of those stories to the goals of social justice, ethical practices, and peaceful coexistence.

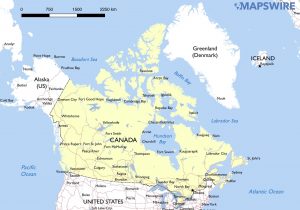

The Americas

Western Canada. From “Stepping into the Past” by Tom Koppel (American Archaeology Magazine [Fall 2016] Vol. 20 No. 3).  13,000-year-old footprints have been found on a remote island in western Canada, demonstrating that people were living on the Pacific Coast during the Clovis period (approximately 13,000-11,000 years Before Present). These are thus the oldest footprints ever found in North America. Significantly, their location on Calvert Island (off the Canadian mainland midway between Vancouver and southern Alaska) is “very different from the numerous sites where Clovis artifacts have been found. Anyone living there toward the end of the Ice Age must have adapted to a marine ecosystem and travelled by watercraft. The footprints, therefore, may help in understanding how and when some of the earliest settlers arrived in the Americas in late Pleistocene times.”

13,000-year-old footprints have been found on a remote island in western Canada, demonstrating that people were living on the Pacific Coast during the Clovis period (approximately 13,000-11,000 years Before Present). These are thus the oldest footprints ever found in North America. Significantly, their location on Calvert Island (off the Canadian mainland midway between Vancouver and southern Alaska) is “very different from the numerous sites where Clovis artifacts have been found. Anyone living there toward the end of the Ice Age must have adapted to a marine ecosystem and travelled by watercraft. The footprints, therefore, may help in understanding how and when some of the earliest settlers arrived in the Americas in late Pleistocene times.”

American Southeast. From “Remote sensing and machine learning reveal Archaic shell rings” by A’ndrea Elyse Messer (Penn State News, August 19, 2021). Shell rings and shell mounds left by Indigenous people 3,000 to 5,000 years ago have been found in dense coastal forests and marshes of the American Southeast. Previously undiscovered shell rings have recently been located by an international team of researchers, using deep machine learning to assess remote sensing data. What they will uncover with these new technologies may well “lead to a better understanding of how people lived in that area and a way to identify other, undiscovered shell rings.” As the archaeologists note, “The rings themselves are a treasure trove for archaeologists… Excavations done at some shell rings have uncovered some of the best preservation of animal bones, teeth and other artifacts.” Further, because shell rings indicate commerce centers, they can provide significant “information on social constructs, politics and foraging.”

Guatemala. From “Sediment Study Measures Population of Maya City in Guatemala,” Archaeological Headlines by Jessica E. Saraceni (Archaeology Magazine, July 7, 2021). A study by researchers at McGill University in Montreal have “found that the Maya inhabited the area [of Laguna Itzan in Guatemala] some 650 years earlier than previously thought, and continued to live in the city of Itzan after the so-called Maya ‘collapse’ between A.D. 800 and 1000, when the area was believed to be deserted.” The study focused on measurement levels of organic molecules from human and animal feces. Despite drought conditions that caused a population decline in three significant time periods – 1350 to 950 BCE; 90 to 280 CE; and 30 to 900 CE – and a very wet period between 400 and 210 BCE, the study team “recorded a low level of fecal stanols in the lake sediments at a time when archaeological evidence indicates there had been a large population living in the city.” This led to the hypothesis that “the Maya may have adapted to changes in climate conditions by diverting human waste from the lake and using it as a fertilizer for their crops.”

Europe

Finland. From “DNA Offers New Insight into Early Medieval Grave in Finland,” Archaeological Headlines by Jessica E. Saraceni, August 2, 2021. In Finland, the contents of the so-called Suontaka grave have been reexamined by University of Turku archaeology researcher Ulla Moilanen and her colleagues.  The 1,000-year-old grave, which held human remains, a sword with a bronze handle, a second weapon, and jewelry typically associated with women’s clothing, was originally believed to hold the remains of a man and a woman, or a woman who had been a warrior or leader. The new study, which included DNA analysis by Elina Salmela of the University of Helsinki, indicates significantly that the grave’s inhabitant was just one person – with Klinefelter syndrome, a condition in which the individual carries the sex-chromosomes XXY. Such people “may be anatomically male, but may also experience breast growth, diminished muscle mass, and infertility.” The person in the Suontaka grave, according to Moilanen, was not only highly respected but may not have been considered to be strictly male or female. The bronze-handled sword was apparently added to the grave sometime after the original burial, which further demonstrates the high regard given to the deceased after his/her death.

The 1,000-year-old grave, which held human remains, a sword with a bronze handle, a second weapon, and jewelry typically associated with women’s clothing, was originally believed to hold the remains of a man and a woman, or a woman who had been a warrior or leader. The new study, which included DNA analysis by Elina Salmela of the University of Helsinki, indicates significantly that the grave’s inhabitant was just one person – with Klinefelter syndrome, a condition in which the individual carries the sex-chromosomes XXY. Such people “may be anatomically male, but may also experience breast growth, diminished muscle mass, and infertility.” The person in the Suontaka grave, according to Moilanen, was not only highly respected but may not have been considered to be strictly male or female. The bronze-handled sword was apparently added to the grave sometime after the original burial, which further demonstrates the high regard given to the deceased after his/her death.

Hungary. From “Contents of Bronze Age Burial Urn from Hungary Examined,” Archaeology Magazine, July 29, 2021, and “Remains of twin fetuses and wealthy mom found in Bronze Age urn,” Laura Geggel, Live Science, July 28, 2021. A burial urn from the Vatya culture in Hungary has yielded evidence of the elite status of a woman who had moved to the area in order to marry. The urn, one of many found in a Bronze Age cemetery discovered at a construction site near Budapest, contained the cremated remains of a woman between the ages of 25 and 35 and twin infants; this was the only urn in the sample study that contained more than one person, suggesting that the woman most likely died near or shortly after the birth of her babies. An analysis of the woman’s teeth showed that she had been born somewhere in Central Europe and moved to the find site between the ages of 8 and 13. The urn also contained a bronze neck ring, a gold hair ring, and bone pins or needles, further evidence of her movement in childhood (the gold hair ring being a wedding gift and the other objects originating in her birthplace). The Vatya culture thrived from about 2200 to 1450 BCE. The woman had married into this “complex culture, with settlements supporting agricultural farming and livestock, an economy invested in local and long-distance trade.” The evidence supports previous research that “women in Europe – especially high-status ones – married outside their local communities since at least the late Neolithic or the Copper Age (about 3200 B.C. 2300 B.C.). . . Perhaps these marriages were crucial to the emerging elite ‘in order to institute or reinforce political powers and military alliances, but also to secure routes [and] economic partnerships.’”

Conclusion

These examples illuminate several things about our ancestors that contribute to today’s pursuit of social justice and acknowledgment of our shared humanity:

- The footprints from Western Canada expand our understanding of the original inhabitants of North America and show that these ancestors were adaptable to different environments and traveled far distances. They are to be admired and respected.

- The archaic shell rings of the American southeast further expand our understanding of our continent’s original Native inhabitants vis-à-vis commerce, politics, and culture. Paying attention to these kinds of discoveries and educating the public about them help to raise our level of appreciation of the non-white aspects of our culture and history and of people of color who were talented, intelligent, and hardworking.

- The discoveries in Guatemala question a longstanding theory about population decline and show in contrast how the Maya may have been highly creative in their use of human waste to survive hard times. This particular study not only highlights the intelligence of ancient peoples but also shows one way in which the science involved in archaeological excavations pushes our knowledge forward in significant ways.

- The grave find in Finland inspires us to revere, respect and honor individuals who are different from ourselves, especially when it comes to gender identity.

- The burial urn from the Vatya culture of Hungary tells a moving story about a woman not only who most likely died giving birth but who was lavishly honored at her death. Through her story we learn about ancient cultures that were in many ways highly sophisticated but which, on the other hand, used women for political, economic, military and social reasons.

We can find many other examples from around the world of the important link between archaeological discoveries and our yearning for social justice; the above reports are a mere snapshot of what is going on in archaeology and related fields.  The importance of every country to support archaeological excavations to the greatest extent possible cannot be overstated. Ever-improving technologies allow investigators to conduct research without the destruction of sites, which used to be the norm, and objects owned, used and created by women, slaves, Native peoples, children and people of color are now handled with great care and are considered just as valuable as buildings, monuments and cemeteries. All discoveries tell very important stories about the cultures out of which they emerge, and they balance the traditional emphases on elite men, war, conquest, power and exploitation.

The importance of every country to support archaeological excavations to the greatest extent possible cannot be overstated. Ever-improving technologies allow investigators to conduct research without the destruction of sites, which used to be the norm, and objects owned, used and created by women, slaves, Native peoples, children and people of color are now handled with great care and are considered just as valuable as buildings, monuments and cemeteries. All discoveries tell very important stories about the cultures out of which they emerge, and they balance the traditional emphases on elite men, war, conquest, power and exploitation.

For the average person, the work of archaeologists vastly increases our knowledge of ourselves and our fellow human beings, some of them from cultures quite different from our own. New finds come to light every day that help us to see – in very tangible ways – the wonderful diversity of humanity, the resiliency of human beings of all sorts and conditions to persevere in the face of adversity and, at times, an enormous amount of acceptance of and respect for those who differ from us. Excavations demonstrate in many ways that we are all part of one immense family, and that knowledge in turn helps us to realize how much we need one another and how much we must all pull together to create a more just and peaceful world.