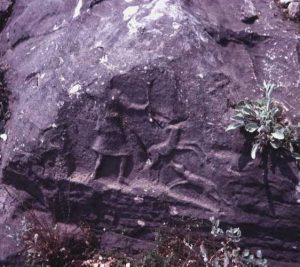

The rock reliefs carved on the acropolis hill at Philippi in northern Greece are a unique archaeological artifact that raise a number of important questions for the history of Christianity, the role of women in the church (and hence the West) and the legacy of St. Paul. The reliefs – which depict primarily the goddess Artemis and unnamed women (possibly priestesses) – number approximately 200 and are dated by archaeologists to the end of the second and beginning of the third century of the Common Era (CE).  This means that these images associated with a cult to a strong female deity were created over 150 years after St. Paul visited the colony preaching the “good news” of the man Jesus known as the Christ.

This means that these images associated with a cult to a strong female deity were created over 150 years after St. Paul visited the colony preaching the “good news” of the man Jesus known as the Christ.

It is generally men who were presumed to create works of art in antiquity. Here we will argue that it may have been primarily women who created the rock reliefs at Philippi and why that is important at several levels.

We have touched on the history of Philippi earlier (the cult of Livia and miscellaneous images). Philippi lies on the important Roman road, the Via Egnatia, and had a long history of habitation, with its people revering a number of deities. In 42 BCE, a major military battle took place there, and by 30 BCE Philippi was named a Roman colony by Emperor Augustus.  The site has been professionally excavated since the early 1900s, and the current forum area – on top of the original Greek agora – was probably constructed around 180 CE.

The site has been professionally excavated since the early 1900s, and the current forum area – on top of the original Greek agora – was probably constructed around 180 CE.

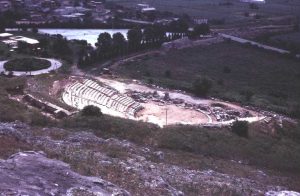

Philippi’s theater dates to the Hellenistic era and was renovated in the second-third centuries CE.  It is the theater that provides the main access to the acropolis hill where the rock reliefs were carved.

It is the theater that provides the main access to the acropolis hill where the rock reliefs were carved.

As we noted in our recent post Women’s Occupations in Graeco-Roman Antiquity, women during the early Imperial era did not just sit idly in their homes all day – they had many roles and responsibilities in their cities and towns. This is equally true at Philippi. Since the rock reliefs are religious in nature, and the entire acropolis hill area is most likely an open-air sanctuary for several different deities, the religious roles played by women come into play. Women in antiquity served as priestesses and other leaders in religious cults as well as lay worshippers; women made costumes and other objects associated with the cult’s rituals, they helped create the calendars for those rituals, they prepared food, and they worked with city officials to determine procession routes and dates of ceremonies. Women taught girls about the deities they were serving, they might participate in healing rituals, they would prepare deceased persons’ bodies for burial, they routinely visited grave sites after a death, and they might craft votive and other offerings for the deceased or the deity. While men too served these functions, it is important to point out clearly that women had important roles in the religious arena, and some roles were held primarily by women.

What, then, specifically would have had to exist at Philippi for women to have been the creators of the rock reliefs? (For a detailed argument, see Abrahamsen, Women and Worship, pages 103-27).

Time.  Women would not have had a tremendous amount of “leisure time” in their lives, but if members of the Artemis cult at Philippi were devoted to the goddess – and if a woman wanted to mark a specific prayer or petition to the goddess on the live rock – she would have made the time to do a carving. A relief may have taken as little as a week or two working an hour or two at a time (and the reliefs vary in quality).

Women would not have had a tremendous amount of “leisure time” in their lives, but if members of the Artemis cult at Philippi were devoted to the goddess – and if a woman wanted to mark a specific prayer or petition to the goddess on the live rock – she would have made the time to do a carving. A relief may have taken as little as a week or two working an hour or two at a time (and the reliefs vary in quality).

Talent. Female devotees of Artemis at Philippi would have had different levels of talent in carving the reliefs. Depending upon how many generations of people carved the reliefs, it is possible that a few women at the beginning did original carvings and mentored their daughters and others in the community to do others. Some women may have created a relief on the occasion of a significant life event then helped another women to create one at that woman’s particular occasion.

Carving tools or instruments. As we’ve seen, women in antiquity owned and managed their own businesses or assisted with those of the men in their families; they would thus have had access to certain tools. It is also possible that Artemis devotees could have borrowed instruments from other devotees, or tools could have been owned in common.

Desire or need.  Some of the life events that may have inspired a woman or family members to honor Artemis on the acropolis hill would have included safe childbirth, a healing event, coming of age, marriage or death. Any of these may have moved a devotee to carve a relief, while relatively minor or routine events would more likely have been acknowledged through less expensive or smaller votive offerings such as food, small objects, flowers or small coins.

Some of the life events that may have inspired a woman or family members to honor Artemis on the acropolis hill would have included safe childbirth, a healing event, coming of age, marriage or death. Any of these may have moved a devotee to carve a relief, while relatively minor or routine events would more likely have been acknowledged through less expensive or smaller votive offerings such as food, small objects, flowers or small coins.

Physical strength. There is artistic, archaeological, physiological and historic evidence from antiquity and other agrarian cultures that adult women had the upper-body strength to do a wide range of activities – from carrying children, water and other heavy objects on a daily basis to laying bricks, using a hammer and chisel to create life-size sculptures, to hunting with a bow and arrow.  Therefore it is not a stretch to believe that the women of Philippi were physically able to create the rock reliefs.

Therefore it is not a stretch to believe that the women of Philippi were physically able to create the rock reliefs.

Access. As mentioned, the theater provided easy access to the acropolis hill. The sanctuary does not appear to have been restricted to women, except perhaps to the Sylvanus sanctuary which was primarily for men, and there are no steep cliffs at the site that would have posed physical danger.

Financial resources. Because women at Philippi and in other Graeco-Roman cities probably had a certain amount of financial limitations – their husbands or other male relatives would generally have controlled most of the finances, and presumably any wages earned by women would have gone toward basic necessities – it is unlikely that women would have had significant resources to commission the reliefs by paid male artists. This is a further argument in favor of women doing the reliefs themselves.

Concluding Thoughts

Exploring the possibility that women, especially female devotees of the goddess Artemis, carved most of the reliefs in the live rock of the Philippian acropolis hill unveils a number of important take-aways.

- We can no longer automatically assume, as has been done in the past over the entire history of humankind, that it was men who were the main or only “players” in a city’s or town’s legacy. We must consider that at least some women in a location had agency to create works of art that had meaning to them.

- Even in highly patriarchal and even misogynist societies women played important, visible and public roles, roles that often benefited the common good.

- Women in cults such as that of Artemis were leaders and mentors. That these cults existed at a time when Christianity was beginning to take hold in the Empire demonstrates the real possibility that female converts to the new religion would have insisted on having leadership roles, contrary to the mainstream, traditional argument that it was men who always held leadership positions and institutional power.

- Devotion to a deity such as Artemis, whose spheres included the protection of women in childbirth and of young children, the next generation, and the respect given to that devotion and that deity by the larger community shows the significance of those life-giving values to the community. In other words, while we in the West, steeped in the adulation of our male forebears and heroes, have traditionally viewed ancient goddesses as merely “fertility deities” and deities worshipped by women, the power of these goddesses to give, protect and preserve life – in the minds of ancient peoples – is paramount. A community could not survive or thrive without the life-giving power of female deities – and of the real-life women of that community. Male deities like Zeus, Apollo, Dionysos, Serapis, Sylvanus and others had attributes important to the community, but they did not bring forth life or sustain it in the same ways attributed to the goddesses of antiquity.

Resources

Abrahamsen, Valerie. “Burials in Greek Macedonia: Possible Evidence for Same-Sex Committed Relationships in Early Christianity,” Journal of Higher Criticism, Vol. 4, No. 2 (Fall 1997) 33-56.

Abrahamsen, Valerie A. Women and Worship at Philippi: Diana/Artemis and Other Cults in the Early Christian Era. Portland, ME: Astarte Shell Press, 1995.

Abrahamsen, Valerie. “Women at Philippi: The Pagan and Christian Evidence,” Journal of Feminist Studies in Religion, Vol. 3, No. 2 (Fall 1987) 17-30.

Abrahamsen, Valerie A. “Women Artisans in the Service of the Church,” Sisters Today, Vol. 65, No. 2 (March 1993) 96-103.

Bakirtzis, Charalambos and Helmut Koester, eds. Philippi at the Time of Paul and after His Death. Harrisburg, PA: Trinity Press International, 1998.