Happy Black History Month! In this and the subsequent blog post, we will be exploring African Americans in Vermont. As many people are aware, Vermont is among the whitest states in the Union. Some of us white Americans, and many non-white Vermont residents, would love to see this change and are committed to diversity and anti-racism efforts. There are attempts throughout the State not only to bolster our economy, attract young people and families, and create good jobs but also to make this beautiful part of the country a destination spot for people of color.

There are fascinating social, economic and historical reasons for why African Americans and other people of color have not felt the pull toward Vermont; we will trace some of those reasons in Part I, as well as areas that still need attention and improvement. In Part II we will examine some of the positive things taking place to improve the lives of African Americans in Vermont ways in which we are attempting to eradicate racism and intolerance.

It is hoped that this modest attempt to bring some of these factors to light will assist in the ongoing battle against racism, bigotry and discrimination AND will help attract people of color, especially African Americans, to this tiny but important and beautiful State.

It is hoped that this modest attempt to bring some of these factors to light will assist in the ongoing battle against racism, bigotry and discrimination AND will help attract people of color, especially African Americans, to this tiny but important and beautiful State.

The History behind Vermont’s Whiteness

In a podcast on Vermont Public Radio’s “Brave Little State” on March 3, 2017, authors Angela Evancie and Rebecca Sananes addressed the questions, “Why is Vermont so overwhelmingly white? And how does that affect all of us?” (The authors noted right off the bat that the original Vermonters were Native Americans and directed readers to the podcast they had done on the Abenaki people a few months earlier.)

Several reasons were given. First, there is the “push and pull” factor. Most immigrants, the authors note, are attracted to places where there are others like them, or jobs, or other “pulls.” As far as African Americans go with regard to Vermont, “There were no jobs, there was no African-American history, heritage, culture to attract African-Americans to come to the state to settle,” according to Sam McReynolds, a professor of sociology and the chair of the Department of Society, Culture and Language at the University of New England. After Emancipation, former slaves could not afford to travel all the way to Vermont; they often ended up in urban areas that offered work in industry. By contrast, it was northern European and Canadian immigrants that staffed the mills and quarries of Vermont; blacks were not in that labor pool. As McReynolds notes about post-World War I migration throughout the US, “So this migration is just phenomenal in number and scale and diversity and range of places. . . And … it went everywhere but Vermont.”

Second, while Vermont offers certain incentives for entrepreneurs and new businesses, these endeavors are almost always on a small scale – artisan farming and local stores and shops, for instance. These by nature employ only small numbers of workers, not enough to allow for much diversity.

The podcast authors note an additional factor that works against attracting African Americans: a “whiteness factor” that may be uncomfortable for many of us to admit. According to Robert Vanderbeck of the University of Leeds, in a 2006 paper, “Vermont and the Imaginative Geographies of American Whiteness,” Vermont has historically promoted “Yankee whiteness,” the recruitment of white farmers, the push to attract second home-owners, and marketing to tourists. These tendencies run smack into our otherwise progressive and inclusive impulses. “Yankee whiteness” is hard to define but is a type of whiteness that people of Italian, Greek and Jewish backgrounds might not feel comfortable with. When farmers were needed around the turn of the 20th century at a time that many Vermonters were leaving their farms, recruitment was focused on Scandinavians and Germans from the upper Midwest – not southern African Americans.

As far as second home-owners goes, the recruitment was explicit. According to Vanderbeck, “In the 1930s, Vermont’s beloved writer and activist Dorothy Canfield Fisher was hired by the Vermont Bureau of Publicity to write an official invitation to potential buyers.” The invitation was explicitly directed at school teachers, college professors, doctors, lawyers, musicians, writers, artists – that is, those who “earn their living by a professionally-trained use of their brains.” While this could have applied to a certain number of African Americans in the US at that time, the recruitment efforts were obviously not in that direction.

As far as second home-owners goes, the recruitment was explicit. According to Vanderbeck, “In the 1930s, Vermont’s beloved writer and activist Dorothy Canfield Fisher was hired by the Vermont Bureau of Publicity to write an official invitation to potential buyers.” The invitation was explicitly directed at school teachers, college professors, doctors, lawyers, musicians, writers, artists – that is, those who “earn their living by a professionally-trained use of their brains.” While this could have applied to a certain number of African Americans in the US at that time, the recruitment efforts were obviously not in that direction.

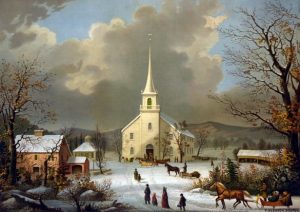

Finally, tourism: the prevailing publicity about the attractiveness of Vermont has traditionally included “white faces, and white snow … white steeples on churches and the so-called white New England village,” according to Vanderbeck.  When regarded so directly, it becomes tragically clear that we have had severe blind spots in our normally progressive and inclusive values.

When regarded so directly, it becomes tragically clear that we have had severe blind spots in our normally progressive and inclusive values.

Today a few cities and towns in Vermont have witnessed some growth in the numbers of blacks, Hispanics, and Asians. Currently, according to the 2013-2017 American Community Survey data from the US Census, the African American population in Vermont is now 1.1%. This is up slightly from that of the 2010 census, when the percentage was only 1. This slight growth is not outwardly visible when walking down the streets of most of our cities but, as pointed out by Curtiss Reed, Jr., Executive Director of the Vermont Partnership for Fairness and Diversity, our schools are a different matter: “Go into the schools — places like Brattleboro, Rutland, Burlington — and you’ll see young people of color. That’s Vermont years from now.”

Setbacks and Areas for Improvement

While the increase in diversity is a positive development, it also – perhaps inevitably – comes with backlash. Periodically reports emerge from our state and towns of racist or potentially racist or antisemitic incidents (since racism and antisemitism often go hand-in-hand): an alleged racist death threat in Brattleboro in April 2018; racist and antisemitic incidents in southern Vermont, as well as opposing opinions of the Black Lives Matter movement; the increase in hate crimes in Vermont, especially hate crimes around race.

The rate of incarceration of blacks in Vermont has recently been examined as an area of great concern. A 2017 article by Justice for All found that “nationally, African Americans are incarcerated at five times the rate of whites across the nation. In Vermont the ratio is even higher at 10 times the rate of whites across the nation. In fact, Vermont is the highest in the nation with one in 14 of all African American adult males in state prison.” This is disturbing, needless to say!

The article continues, “State officials know that in the aggregate African Americans are not disproportionately likely to commit certain drug crimes, but they nevertheless are more likely to wind up in prison where whites convicted of similar offenses may get alternative outcomes.” This situation is apparently due to traffic stops: “the disproportionate number of traffic stops and searches of African Americans by law enforcement.”

Some steps toward racial equality and fairness in policing and law enforcement have been taken in the past few years to address this and other inequities. In May 2017, Gov. Phil Scott signed a bill that establishes a “racial justice oversight board,” designed to examine systemic biases in law enforcement practices and the court system. Vermont Attorney General T.J. Donovan testified in August 2018 about progress being made on expungements for low-level offenses, an issue on which Donovan has taken a leading role.

Some steps toward racial equality and fairness in policing and law enforcement have been taken in the past few years to address this and other inequities. In May 2017, Gov. Phil Scott signed a bill that establishes a “racial justice oversight board,” designed to examine systemic biases in law enforcement practices and the court system. Vermont Attorney General T.J. Donovan testified in August 2018 about progress being made on expungements for low-level offenses, an issue on which Donovan has taken a leading role.

A final example of how we in Vermont have some areas that need improvement is the very disturbing case of former State Representative Kiah Morris. Morris was the only black female in the state legislature. The reason she is now “former” is that she and her family were emotionally harmed by months of racial harassment.

Starting in March 2016, Ms. Morris, who represented the Bennington area, began receiving anonymous messages, including racist tweets. According to the State Attorney General’s Office, which investigated the situation after she stepped down from her position, “The harassment continued for months and involved instances of online harassment, theft and vandalism.” In a press conference, AG T.J. Donovan stated, “The harassment was often based on Kiah Morris’ ‘race and gender’ and carried out ‘in a context of vicious racial harassment.’” Some of the comments that she and her family received, even after her resignation, included the following:

- “The only place you’re going to be safe is Africa.”

- “Thanks for resigning, now please move out of my state.”

- “Whites will be ready for the war.”

At least one of the perpetrators was identified as Max Misch, an avowed white nationalist from the Bennington area. Because of the hateful messages he sent Morris over the course of two years, she was granted a protective order against him in 2016. (Update: Misch was arrested on February 6, 2019, on charges of purchasing and possessing high-capacity gun magazines that were outlawed last year.)

Unfortunately, AG Donovan did not feel he could press charges on the harassment of Morris because of First Amendment rights. He explained, “The court tells us that where speech involves public officials or [matters] of public concern the First Amendment tolerates a great deal of speech that is hateful and offensive.” Donovan did, however, launch a statewide Bias Incident Reporting System to encourage law enforcement to share reports of hate speech incidents for civil investigation. As Morris noted, the abuse she was subjected was “historically rooted in a legacy of white supremacy, misogyny and inequity.” It is this legacy that we in Vermont, and throughout our nation, must continue to combat tooth and nail.

In Part II of our examination of blacks in Vermont, we will take a look at the ways in which Vermont is attempting to foster racial equality, to make Vermont as attractive as possible for underrepresented people to put down roots here, to enhance multicultural tourism, to improve life for students of color, and to increase racial diversity in hiring, including in town government. Illuminating such efforts is not so much to brag about what we are doing but rather to educate and encourage; we all have a stake in this issue – and we can all make positive contributions.