The Bible: a vitally important text in Western history. Contrary to some popular misperceptions: not one book but many; not written in King James English but in at least three ancient languages; and not originally written but rather passed down orally for generations.

It should go without saying, then, that translating a collection of ancient texts such as the Bible is neither easy nor trivial. Over the next few weeks, we will look at how the Bible came to be, explore the history of Bible translation and transmission, the challenges that translators have faced over the centuries, and the efforts of more recent scholarly groups in bringing the Bible responsibly to modern audience

Overview of Biblical Texts

The “book” that we generally call the Bible is actually a collection of ancient texts revered as holy or sacred primarily by the Jewish and Christian religions. The collection of texts that make up the Bible differ depending upon the group, and the way in which we refer to various sections of the Bible are called different things now as well.

- Jews revere the first five books of the Bible – Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy – as the Torah. The original language of these texts is Hebrew.

- Traditionally those five books plus 34 others written in Hebrew have traditionally been called the Old Testament. More recently, however, out of respect for Judaism, this collection is referred to as Hebrew Scriptures.

- Fifteen additional texts that were all in the Septuagint (discussed below) is the Apocrypha (meaning “hidden things”), texts written later than most of the Hebrew texts but prior to the books of the New Testament (see below); hence they are “intertestamental.” These texts are not included in the standard Bible of Protestants but are included in the Bible of Roman Catholics and were widely known to ancient scholars.

- Christians – Roman Catholics, Eastern Orthodox, Anglicans and Protestants – revere the Hebrew Scriptures as well as the 27 texts of the Bible written originally in Greek. This is widely referred to as the New Testament. The main focus of the New Testament is the life and ministry of Jesus of Nazareth and the origins of the Christian faith in Israel, Greece, Italy and other countries around the Mediterranean.

While the Bible – all these texts written originally in other languages – may be considered the “Word of God,” it should be apparent that it was compiled by human beings over many centuries. As we will also note below, the perspective of most of the texts was male, and the final authors and editors were generally men. This is significant when we examine the messages, ethical precepts, and theology that were imparted by the translations of the ancient texts into King James English as well as modern languages.

Transmission: From Oral to Written

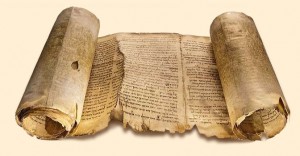

Biblical scholarship over the past century has revealed that the stories in the Bible were originally handed down orally. For the Hebrew Scriptures, we should picture nomadic people around campfires passing down their people’s history to their children. When the stories were first compiled in written form, they were written on long scrolls. The codex, the ancestor of our book, was only invented in the second century CE. Neither scrolls nor codices were generally available to common people but rather to religious leaders and in libraries. Trained cantors would read from these to the people during the liturgy – which is a different model than ours today, where we read the texts ourselves or laypeople with little liturgical training per se read to the congregation.

In the third century Before the Common Era (BCE), Jewish scholars came to Alexandria, Egypt, over the course of about two centuries and translated the Hebrew texts into Greek for the first time. This became known as the LXX or Septuagint version of the Hebrew Bible based on the legend that it took 72 scholars 72 days to produce the translation. (LXX is Roman numerals for 70; how 72 was reduced to 70 is unknown.) This is the version of the Scriptures that the people of Jesus’ time, including St. Paul and the Gospel writers, would have been familiar with.

Like stories of the Jews, the New Testament stories also originally circulated orally, including among women. The earliest New Testament writings are the authentic letters of St. Paul, written in Greek in the 50s of the Common Era (CE), with the Gospels being written between ca. 70 and 100 CE. Acts of the Apostles was written about 100 CE, probably as a sequel to the Gospel of Luke. Other literature of the Bible was written as late as 120 CE.

As far as existing documents go from this early time, “Not a single autograph of any book of the New Testament has been preserved,” in the words of the late Harvard professor Helmut Koester. We have a fragment of the Gospel of John written in the early second century CE, but beyond that all that exist are copies written after about 300 CE, which we will examine in some detail below. This absence of authentic texts from the period in question makes translating Biblical literature very challenging and open to various interpretations.

It was in the fourth century CE that Biblical scholar Jerome translated the LXX into the Latin Vulgate. In more modern times, the printing press was a major impetus to the translation of the Bible. The first full book to be printed was the Gutenberg Bible in 1455-56. In 1525, William Tyndale produced an English translation from Hebrew and Greek. Martin Luther translated the Bible into German around 1522; the significance of this for the Reformation was immense – people could now read the Bible for themselves in their own language (if they were literate) instead of leaving it up to the priests to translate it for them from Latin.

The Bible was translated into the King’s English in 1611 (King James Bible or KJV), from which we get some of our most memorable and beloved Bible passages, such as the text of Handel’s Messiah]. As we will see later, translations continue in languages all over the world.

Bible Manuscripts

A number of important ancient manuscripts have been discovered in the past 200 years or so. Martin Luther, the British translators of the 17th century, and others did not have access to these amazing documents. Thus modern scholars have many more sources to draw on.

Some of the most significant manuscripts are:

- Codex Vaticanus (Codex B) dates to the mid-4th century and is housed in the Vatican library. Probably written in Alexandria, Egypt, it is one of the most valuable uncial manuscripts of the Bible (“uncial” means written in all capital Greek letters with no spaces between words.) This codex was written with few mistakes and is quite reliable as a source.

- Codex Alexandrinus (Codex A) dates from the 5th or 6th century and is now housed in the British Museum. Alexandrinus contains the entire Bible (although with major gaps) as well as the early Christian letters I and II Clement. This codex is also deemed very reliable.

- Codex Sinaiticus (Codex Aleph or S) is from the 4th or 5th century. It was found on Mount Sinai in 1844 and contains almost the entire New Testament, much of the Hebrew Scriptures in Greek, and the Epistle of Barnabas and the Shepherd of Hermas, two important early Christian writings. Sinaiticus is a valuable witness but not as reliable as Vaticanus or Alexandrinus.

- Codex Bezae (Codex D), a great “Western” manuscript of 5th or 6th century, is now at the University of Cambridge in England. It contains the Gospels and Acts.

- The Chester Beatty III papyrus fragments of the 3rd century contain the middle part of a papyrus codex of the Revelation of John.

- Various other papyri also aid translators: several from Oxyrhynchus, Egypt; several from the collection of Geneva philanthropist Martin Bodmer; and Papyrus Rylands 5 (which dates to approximately 200 CE) and 457 (dating to the first half of the second century).

In some versions of the Bible, the abbreviations of these manuscripts can be found as footnotes showing which terms are found in which manuscripts.

How were these manuscripts created and preserved so that scholars can still use them so many centuries later? For the most part, Biblical texts were copied by monks and nuns working in scriptoria. Since these were fallible human beings and the conditions were far from ideal, mistakes and (mis)interpretations took place. In many manuscripts the words flowed together without spaces or punctuation, leading to different interpretations: the translator had to guess at where a word or phrase ended and the next one began! There were also common errors anyone might make when copying something by hand: omissions, repeated words, misspellings, word contractions, etc.

More serious errors were “intentional changes introduced by scribes and before them by owners of manuscripts, who wished to improve or to correct their text by reference to some other manuscript that they preferred or to some familiar quotation of a text” (F. Grant). One of the most serious changes, theologically, is the insertion of “begotten” in John 1:18: the text changed to “only begotten God” from “the only Son” in many manuscripts.

Most later manuscripts – several thousand of them – were so-called minuscules, mostly written in the late Middle Ages. These were written in cursive with spaces and punctuation with which we’re familiar today. They are mostly mixtures of the older textual traditions mentioned above.

Summary

As we can see, many factors go into what makes the Bible (or Bibles) in our day:

- Dozens of texts originally circulated orally then written down centuries ago;

- Languages spoken and written that are not widely taught anymore in schools (and in one case, Latin, a “dead” language);

- Church leaders with definite theological notions and oftentimes the power to make changes in texts that do not necessarily reflect the original intent;

- Texts written in all capital letters and no punctuation, and which no longer exist;

- Books copied by monks and nuns – fallible human beings – without benefit of electricity, paper or any other modern tools;

- Codices of varying quality, copied much later than the original texts, which contain only portions of the Bible.

In our next post, we will examine a few examples of challenging textual translations and how different interpretations have affected not only theology but also the lives of millions of human beings.

Resources

Funk, Robert W. Honest to Jesus. New York: HarperSanFrancisco, 1996.

Grant, Frederick C. “The Text of the New Testament,” Encyclopedia Americana, Vol 3, 695-99. Danbury, CT: Encyclopedia Americana Corporation, 1984.

Koester, Helmut. Introduction to the New Testament. Volume Two: History and Literature of Early Christianity, second ed. New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1982, 2000.

MacDonald, Dennis R. The Legend and the Apostle. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1983.

Pervo, Richard I. Dating Acts: Between the Evangelists and the Apologists. Santa Rosa: Polebridge Press, 2006.